You’ve just introduced students to the idea of subtraction with regrouping. You’ve put the students into small groups to work together to solve 5 problems. Aaron has contorted himself around his chair and appears to be playing with something – whatever it is, he is not interacting with his group. He spots you looking at him and he immediately asks if he can sharpen his pencils. You gently say, “No, Aaron. It is time to work with your group on the regrouping problems.” Aaron pouts and crosses his arms in a huff. Inwardly, you sigh. You’ve seen this behavior over and over again.

One possible explanation for Aaron’s behavior is that he is a perfectionist.

We often think of perfectionists as supremely confident individuals to whom most things seem to come easily. We think of perfectionism as ultimately leading to success. The truth is these stereotypes are rarely, if ever, true.

Perfectionists are often anxious and fearful. They fear being seen as a failure. These fears can manifest themselves in the classroom in many ways.

- Doesn’t take risks in learning

This is the student to always seems to keep to the easier “stuff”. He will choose books below his instructional reading level. She will copy others’ creative or open-ended answers for fear of having a product or answer that is different from others. - Avoids tasks, especially challenging new work

This is the student who seems to ask to use the bathroom whenever he is asked to do something new in a subject. She regularly starts a different task or continues with a previous task instead of what she was asked to do. - Gives up easily

This is the student who declares, “This is stupid” and gives up. She huffs and pouts and becomes stubborn. - Is exceptionally slow when working

This is the student who draws each letter in a sentence in slow motion. She seems to take forever to get anything done. - Has a meltdown when mistakes are pointed out or when s/he makes a mistake

This is the student who has us tiptoeing around telling him about what he got wrong because we are afraid he will throw a temper tantrum, or she will start shouting and overturning desks. - Uses diversionary tactics

This is the student who tried to get you and the class off-task or off topic. She will ask questions that have nothing to do with the subject at hand. He knows what can get the teacher off on a different subject, telling stories, or reminiscing about something else. When he is successful, the lesson stalls and suddenly it is the end of the class period or it is time for a “special”. - Procrastinates

The student avoids getting started on an assignment or project, or simply doesn’t hand something in. She figures that if she doesn’t get started she won’t be up against the possibility of failure. If he never handed anything in, he can say, “I could have done great on that, but it just wasn’t worth my time.”

Many students are often masters at hiding their perfectionism. We think he can’t possibly be a perfectionist because he doesn’t dress or groom himself well, his desk or locker or backpack is a disaster area, his handwriting is sloppy, or he loses things with alarming regularity. It fits with the stereotypes we have about perfectionists when we think a student cannot be a perfectionist because she is not “perfect” in every area of her life. Yet perfectionists often seek “perfection” in only one or a few aspects of his/her life

How can you spot a perfectionist?

- Look for the behaviors above and watch for patterns in behavior. Being slow at completing an assignment once can be attributed to having a bad day. Twice might be a coincidence, but three times can be a pattern.

- Examine your own stereotypes about perfectionists.

- Think about why a student might demonstrate a particular behavior in that particular time and in that particular place. What is she attempting to get or avoid with the behavior. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking “she just wants attention”. Attention-getting behaviors quite often are far more complex than a simple bid for attention. We have to ask ourselves why he wants that kind of attention at that particular moment.

What can I do if I think one or more of my students are perfectionists?

- Model making mistakes

When I first started teaching, I would be horrified if I made a mistake when students could see it. I came to realize that often children do not have particularly good role models for making mistakes. They may have adults in their lives who do not ever seem to make mistakes, or who use any or all of the coping strategies listed above. It can be empowering for students to see an adult make mistakes without the world coming to an end. - Model how to recover from making mistakes.

Showing students that you can laugh at your mistakes or that you can learn from them is a valuable lesson for them. I used to tell students to carefully watch what I was writing on the board and to try to catch me in making a spelling mistake. It provided an opportunity to apply phonics skills and kept students engaged, even if they were only engaged in seeing if I goofed. When I student caught me in a spelling error, I would ask the student to spell the word for me while I corrected my mistake on the board. Then I’d write his name on the board with a tally mark after it. At the end of the lesson, or the day, or the week (it depended on the age of the students), I would ask everyone who caught me in a mistake to take a bow while the class gave them a round of applause. - Demonstrate thinking about how to learn from mistakes.

Pretending to make a mistake when doing that subtraction with regrouping problem on the board, and thinking aloud about how to both recognize the mistake and how to learn from it helps students understand the process. Try marking papers with the number correct over the number possible on the page. For example, if there were 12 possible answers on an assignment and the student got 3 wrong, write 9/12 as the score rather than a percentage or a letter. This puts the focus on what the student did right and not on what s/he did wrong. Allow students to discuss with other students where they went wrong. You can try putting them into small groups based on what they got wrong (Everyone who got sidetracked with problem 11 meet here) or in mixed groups to review each part of an assignment. You can even have a discussion on what may have happened on a particular part of an assignment. For example, “I noticed that about half the class had difficulty with ___. Who will share with the class their strategy that helped them figure out what to do instead?” This latter can only happen in a class where students have become comfortable with making and learning from errors. - Anticipate common errors and show students how to avoid those.

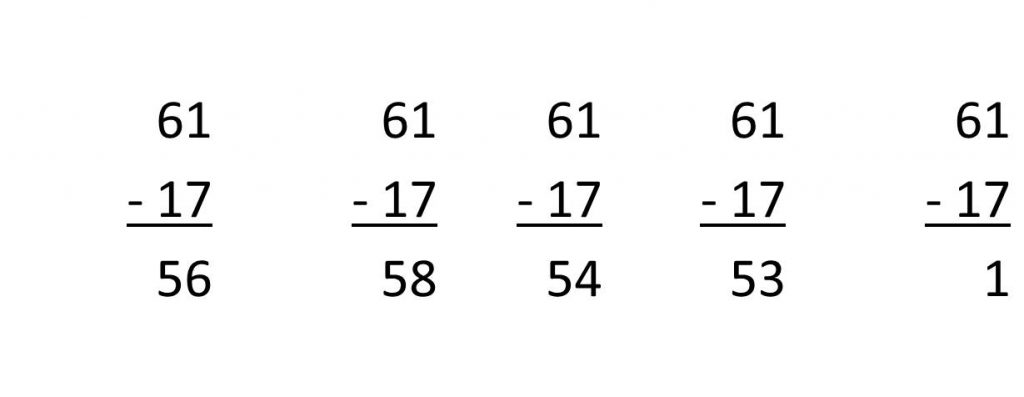

Teachers can anticipate the ways that students will get new concepts wrong. With the subtraction with regrouping example, we can predict that students will make these common errors. If we can anticipate that someone will likely make these mistakes we can incorporate that into our lesson. For example, say, “A lot of times people get mixed up about how exactly to subtract with regrouping. I’m going to write some mixed up problems on the board and I want you to try to figure out where I went wrong. Now don’t get tricked!”

- Don’t get tricked vs. don’t make a mistake

Mistakes are scary to many students, but avoiding getting tricked is a game. When a teacher frames “mistakes” as trying to avoid getting tricked, it casts the possible mistake in the light of a puzzle. Children who might react negatively to making a mistake often see puzzles as fun to do, and delight in outwitting the task or teacher. - Try to set aside our own perfectionist tendencies.

Teachers are no different from other human beings. There are many of us who are perfectionists, who fear making mistakes, and who see our own fallibility as something shameful. We can convey those beliefs to students. If we are more comfortable with making mistakes, we can convey that attitude as well.

We often do not think of THAT student as a perfectionist yet that exact trait may be what makes THAT student do THAT. We can look for the signs of perfectionism and create a class culture that helps students cope with being imperfect and learning from our imperfections.

What went wrong with those subtraction problems?

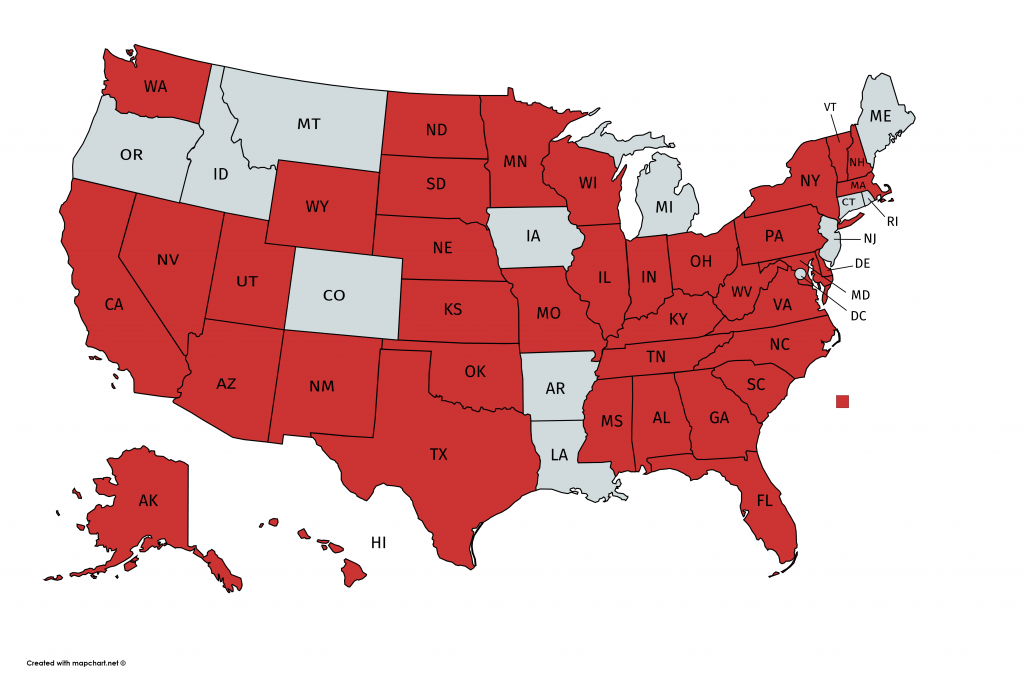

- null

- 61 – 17 = 56: The student subtracted the 1 from the 7, inverting the ones column.

- 62 – 17 = 58: The student added the ones column.

- 62 – 17 = 54: The student regrouped, subtracting 7 from 11, but did not write down the regrouping in the 10s column so he subtracted 10 from 60 instead of 10 from 50.

- 62 – 17 = 52: The student made the 1 a 10 and subtracted 7.

- 62 – 17 = 1: The student added 6+1 to get 7, and 1+7 to get 8. She then subtracted the smaller number (7) from the larger number (8) to get 1.