I do not know any teacher who consciously discriminates against any student for any reason. If you ask a teacher, she will say, “I treat all students well! I want them all to learn!”

In my experience, this is true – all teachers believe they want all students to learn.

Despite this, there is a persistent achievement gap between Black and Brown students and Caucasian students.

We know for a fact that there is no difference in the brains of people. One cannot tell if a brain comes from a person who is Black, Brown, white, male, or female. While there may be individual differences in a person’s ability to learn, that ability is not dictated by the color of the person’s skin or by the person’s gender.

So what is the issue?

We have known something that makes an astounding difference in the education and IQs of students since 1964. It is called the Pygmalion Effect or the Rosenthal Effect after the Harvard researcher who “discovered” it.

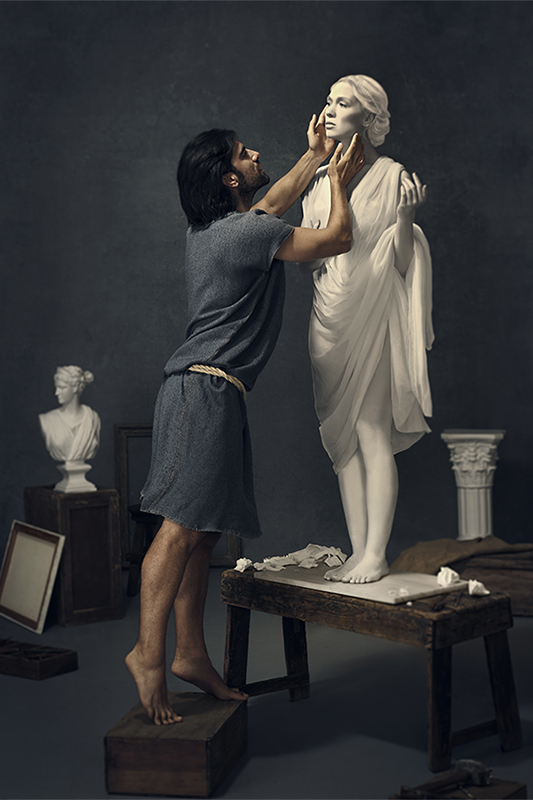

In Greek myth, Pygmalion was a sculptor. He crafted a sculpture of a woman that was so lifelike he yearned to make her his wife. His belief in her reality was so great that Galatea, as he had named the sculpture, came to life.

What Rosenthal discovered was that when teachers believe children are capable, or even more capable than they have previously demonstrated, they blossom. Further, the children’s tested IQ increase dramatically. The greatest increases happened with the youngest children. In fact, some of the first graders in his experiment increased their IQ by 27 points!

Sadly, the converse is true. Students whose teachers believed they were less capable fell further and further behind.

This has been studied many times since the 1960s. It has changed many things about education. Teachers are taught they must have high expectations. The coursework required of prospective teachers has increased dramatically as well. The underlying purpose of these changes is to better prepare the prospective teachers for the classroom, and to ensure that they have the knowledge of subject matter needed to model those high expectations.

The problem is it is not teacher knowledge of subject matter that increases high expectations for students. It is the teacher’s behavior.

I have listened to numerous teachers in three states talk about students. None believed they had low expectations. So how do I know they thought of some students as less capable than others?

There are clues in what the educators said. For example:

- Her parents just don’t care.

- He comes from serious poverty.

- Her family doesn’t speak much English.

- His home life is really chaotic.

- She comes from a broken home.

- He is my behavior student.

- She is my learning disabled student.

- We have a very high number of free and reduced lunch students.

- This is a Title I school.

I have heard all of these statements offered as a reason why a student is not learning.

Yes, none of the situations above are fun, and they can affect students’ emotional well-being. But they do not limit the ability of the student to learn.

Research has shown that teachers make unconscious decisions about the ability of students. They categorize them as “capable” or “less capable”.

The result is that the teacher treats students s/he thinks of more “capable” differently than s/he treats those s/he thinks of as less capable.

Here is a table that shows the behaviors:

| Teacher Actions | “Capable” Students | “Less Capable” Students |

| Calling on students | Calls on often | Calls on less often even when has hand raised |

| Wait time | Gives significantly more wait time | Gives significantly less wait time |

| Types of questions asked | Tends to ask “thinking” questions; higher level thinking (Bloom’s Taxonomy) questions | Tends to ask “recall” type questions; lower level (Bloom’s Taxonomy) questions |

| Allowing corrections | Will prompt student if s/he is wrong Will allow student to correct him/herself | Will move on to another student if s/he is wrong |

| Praising students | Praises student for academic-oriented behaviors | Praises student for compliance to classroom rules or procedures |

| Helping students who don’t understand | Asks student prompting questions, for example: “What do you do first? Now, what do you do next? How will you know . . .” | Demonstrates how to do task Does the problem for student (e.g. math) Gives student answer |

| Greeting students | Greets students by name Talks with students about interests and activities Tone of voice sincere, warm | May nod May not say anything May use backhanded compliment (“I wondered if you’d show up today.”) Tone of voice neutral or sarcastic |

| Informal conversations | Pauses to talk with student about interests or activities Listens to all of student’s story | Pauses for conversation less often Cuts student off Suggests student finish story later |

| Eye Contact | Makes frequent eye contact | Rarely makes eye contact |

In short, the teacher creates a warmer, more welcoming classroom climate for the students s/he has unconsciously categorized as capable, than s/he does for students in the “less capable” category.

Let me be very, very clear: rarely, if ever, do teachers do any of this consciously! Nonetheless, researchers have repeatedly observed teachers engaging in these behaviors.

I have observed this myself in classrooms from elementary to high school – and in every single case, the teacher was one who worked hard at teaching, who focused on student learning, and who believed s/he treated every student equitably. However, s/he did not do what s/he thought s/he was doing.

Research has pointed out several factors that influence teacher’s thoughts about whether or not a student is capable or less capable.

- Having black or brown skin

- Speaking a language other than English at home

- Being labeled as having dyslexia or dyscalculia

- Receiving Title I services

- Having a 504 plan

- Having a physical disability such as being hard of hearing

- Wearing dirty or ill-fitting clothes

- Having poor hygiene

- Living in “that” part of town

- Transferring from a rural or urban school to a suburban school, or an urban school in the “right” part of town

- Being a member of a different religion or denomination than the majority of students

- Being less mature than peers, for example, thumb-sucking or crying about hurt feelings

- Being overweight

- If male, being smaller than peers; if female, being larger than peers

- Having parents who are divorced or who have never married

- Having parents who work blue-collar or pink-collar jobs

If you are like me, about now you are thinking, “OMG! Am I doing this? What can I do to change this?”

When I first learned about this research, I looked at the list of behaviors and felt overwhelmed. I could not change everything all at once. So I thought about which behaviors I thought would most likely affect learning. I decided to focus on how I asked questions. I put a class list on a clip board and made a tally mark by each student’s name when I called on him/her. I did this for each of my classes. (I was teaching middle school at the time.)

It would have been undoubtedly better to ask a colleague to come in and do this kind of tally for me. If you are in a school with an instructional coach, they may be just the person to help.

What I discovered was that I was calling on some students more often than others! Worse, when I looked at who I was calling on, I couldn’t help but think, “Oh, I asked so-and-so that question because I figured he could answer it.” Yikes!

I thought I might force myself to make changes if I had a system to randomly call on students. I know some teachers use popsicle sticks for this. However, I felt popsicle sticks had disadvantages. First of all, the can with the sticks was not as portable as I wanted it to be. Second, I’d seen some teachers who made a production out of choosing a stick so it was slow. And last, popsicle sticks seemed too “little kid” for my big middle school students.

What I needed was something that was portable, fast, and would not be offensive to middle school students.

I decided to make a card for every student. I cut 3”x5” index cards in half and wrote a student’s name on each card.

At that point I realized that if I had only one card per student, the student was likely to listen only until his/her name came up. Then s/he would tune out until everyone else was called upon.

I made another set of cards. This meant that every class had a deck of cards, and every deck of cards had each class member’s name in it twice.

I taught the students the procedure:

- I will ask a question.

- Do not raise your hands.

- I will give wait time.

- I will turn up a card. That student will answer or say pass.

- If the student says, “pass” his/her name is put into the middle of the deck so s/he knows s/he will be called on again soon.

- If the student’s answer is wrong, s/he gets a chance to correct him/herself or the card goes into the middle of the deck.

I had my system. It was portable – in fact it fit into the pocket of my pants or blazer. I could shuffle the cards in front of the students so they knew I wasn’t targeting anyone. I could turn up cards quickly. I used humor with it so those delicate middle school egos were not bruised unduly.

(I enlisted the help of the classes to help make sure I was providing an equal amount of wait time. But that’s another story!)

You may choose to address a different behavior. I hope you will share those ideas here!

Teachers can make students think of learning as something worthy and attainable, or they can make students believe they are incapable of learning. It is easy to do the latter. We even do that without conscious thought! It is more difficult to make sure that ALL think of learning as something they can do. Yet educators can, and must make sure we do this for every single child. Every. Single, Child.

Works Consulted

- Katherine, Ellison. “Being Honest About the Pygmalion Effect.” Discover Magazine. October 28, 2015. https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/being-honest-about-the-pygmalion-effect (accessed June 15, 2020).

- Rosenthal, R, and L. Jacobsen. Pygmalion in the classroom: teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968.

- Sadkur, Myra, and David Sadkur. Failing at Fairness: How America’s Schools Cheat Girls. New York: Simon and Shuster, Inc., 1994.

- Spiegel, Alex. “Teachers’ Expectations Can Influence How Students Perform.” NPR. September 17, 2012. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2012/09/18/161159263/teachers-expectations-can-influence-how-students-perform (accessed June 15, 2020).