I am taking a little break from writing about good rules and poor rules to address a concern I’ve heard frequently over the past several months. What I’ve heard over and over again is people saying that the solution for chaotic schools is to get rid of those students who are disruptive so teachers can work with the students “who want to learn.” These comments have come from those in education, and those outside of education.

I want to start by saying that I can hear the frustration in the voices of those who express these ideas. The teachers who say it are stressed and often bewildered by what is happening. People outside of education are often saying this because it angers them that their loved ones have such a poor work environment, or are expressing nostalgia for the “good old days” when allegedly students behaved in school.

No matter what age one lived in, there have always been disruptive students in the schools. Yes, we did deal with those students differently in the past. They were often urged to drop out of school, even as young as in elementary school. Their absence did make schools more peaceful, but at what cost?

In my grandparents, or even my parents time, it was possible for a person to be functionally illiterate and to still make a decent living for themselves and for their families. There were factory jobs or manual labor jobs where one did not need to read, write, or do math at all, or not at a very high level. That has changed dramatically in the second half of the 20th century and even more so in the first decade of the 21st.

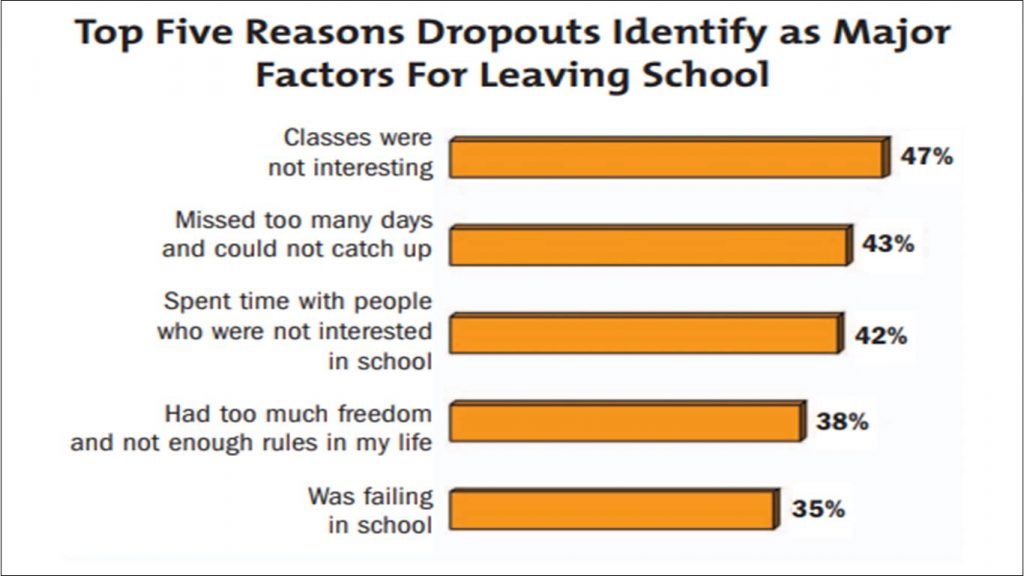

(Bridgeland, Dilulio, & Morison, 2006)

Using figures from a PBS article describing an episode of Frontline called Dropout Nation from 2012, we can see that even six years ago, the cost of dropping out of school is expensive, not just to the drop out but to society as well.

- The average dropout can expect to earn an annual income of $20,241. . . That’s a full $10,386 less than the typical high school graduate, and $36,424 less than someone with a bachelor’s degree.

- While the national unemployment rate stood at 8.1 percent in August [of 2012], joblessness among those without a high school degree measured 12 percent. Among college graduates, it was 4.1 percent.

- According to the Department of Education. Dropouts experienced a poverty rate of 30.8 percent, while those with at least a bachelor’s degree had a poverty rate of 13.5 percent.

- Among dropouts between the ages of 16 and 24, incarceration rates were a whopping 63 times higher than among college graduates, according to a study by researchers at Northeastern University

- When compared to the typical high school graduate — a dropout will end up costing taxpayers an average of $292,000 over a lifetime due to the price tag associated with incarceration and other factors such as how much less they pay in taxes. (Breslow, 2012)

These are dismal figures. Worse, additional research shows that this “by the numbers” snapshot is getting darker, not better.

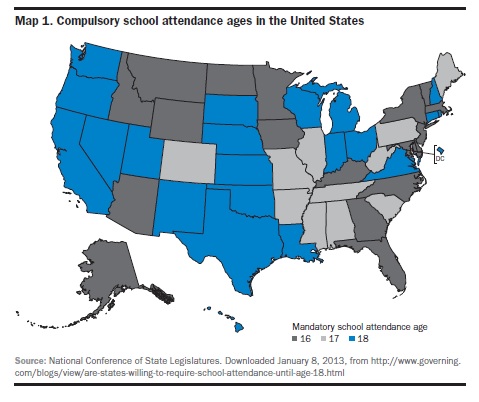

Confusing matters further, each state has set their own age where a student may drop out of school legally.

Age for drop out varies. This figure is in the individual states’ hands. Most have set the legal age at 16. However, fifteen states and the District of Columbia set the legal drop out age at 18. Nine have set it at 17. As of 2011, six states, including Iowa were debating raising the minimum dropout age to 18. In other words, 38 states plus the District of Columbia have or are considering raising the age when a student can legally leave school. (K12 Academics, 2011)

The National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers’ union, advocates for raising the legal dropout age to 21. Why? The NEA cites much of the above information and adds that a study done at MIT shows that more than a quarter of the students considering dropping out of school stay in because of compulsory attendance laws. (National Education Association, 2012)

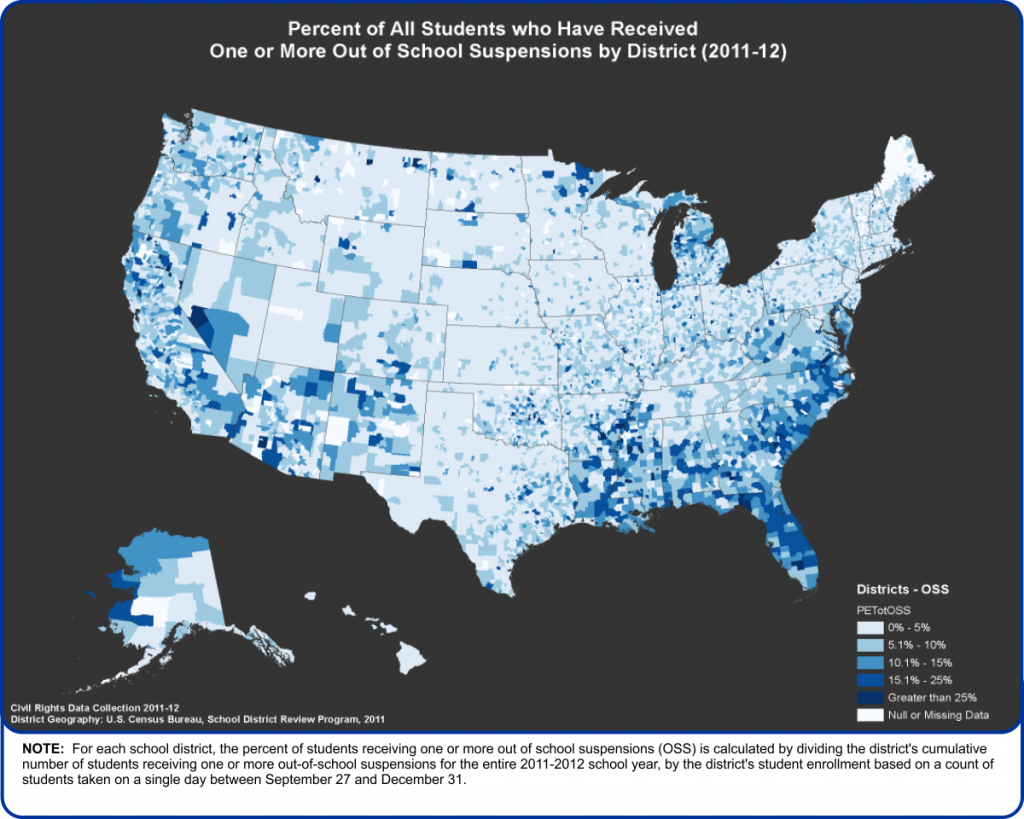

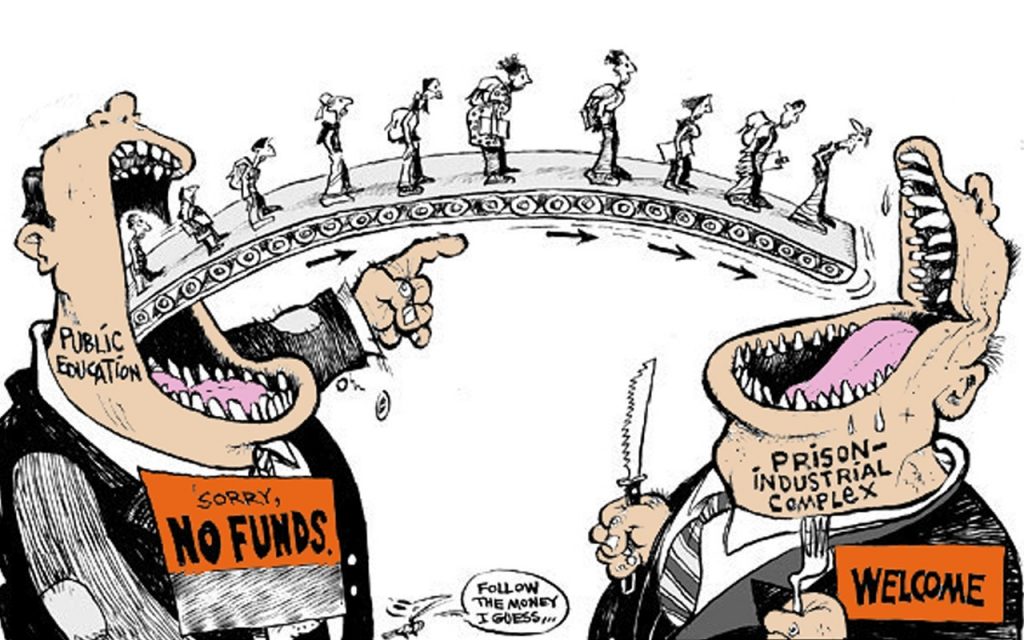

So we see that there is a high cost to the student and to society when young people drop out of school. But that leads us to the next strand of this issue: what is the connection between using in-school suspension, out-of-school suspensions and expulsions and dropping out?

First we have to look at suspension and expulsion, why schools do and don’t use it.

In the aftermath of mass school shootings in the 1990s, new policies were put in place at the federal, state, and local levels regarding students bring guns or other weapons to school, and how we handled violent students. These policies came to be called “zero tolerance” policies because any student who brought weapons to school or who were too violent were expected to be taken out of the school – we were to have no or zero tolerance for such behavior.

I was a school principal when “zero tolerance” became the buzzword in conversations about school discipline. In districts all around mine and across the country, students were being suspended for “offenses” as small as bring a knife in their lunch box to cut up an apple, making their fingers into “guns” and having imaginary gun battles, and bringing their grandfather’s pocket knife to show and tell. I believed that such a strict interpretation of the zero tolerance policies was absurd and I refused to suspend the kindergartener who brought that pocket knife to school, although I did keep it in my desk until his parents could come get it. I was much more concerned with the intent behind the behavior than actually bringing the item to school or playing “cops and robbers”. At that time, I often declared that if someone wanted to take me to court over it, I figured no judge would condemn me. I still stand by that position.

Yet many did not and school suspensions and expulsions rose dramatically. However, during the Obama administration, states and schools were sent a policy memo asking for a more moderate interpretation of the policy requirements. Sadly, after the Parkland shooting, federal level law makers have called for a return to the literal interpretation of “zero tolerance” and for increasingly punitive responses to student behaviors.

We have had two decades to study the results of those zero tolerance policies and to see if they do indeed work. The short answer is “No, they do not work.” Why?

A synthesis of a number of studies shows that schools that have high suspension rates demonstrate low academic performance rates for the school. These performance rates are those measured by whatever academic assessment has been required by the state. Additionally, studies of student attitudes show that schools that have a high number of suspensions have students and families who believe the school to be punitive instead of trying to help students and their families. The students in the studies often cited the reason for a suspended student’s behavior as being rooted in institutional oppression based on race, creed, socioeconomic condition, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. These observations made the students less likely to view the school, its teachers and administrators as sympathetic to the needs of young people, and more likely to be unfair and arbitrary. (Black, 2018)

In other words, the greater the number of suspensions and expulsions in a school, the more poorly the school did academically and in the perceptions of the students and their families.

(Maxwell, 2013)

Further, there is a direct correlation between suspension and the so-called school to prison pipeline. In an article about the reasons why school punishments do not work, Marie Amaro cites an Australian study that found “students were 4.5 times more likely to engage in criminal activity when they were suspended” than when they were simply truant. She further asks, “Jails are full of people who do not respond to the threat of incarceration so why do we think that loss of recess or suspension will change a student’s behaviour?” (Amaro)

To be absolutely fair in this discussion, I must report that I was not the only administrator who disliked the zero tolerance policies and who did not always follow them. However, often the reasons why school leaders did not follow them had to do with another punitive piece of legislation: the 2000 iteration of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. The ESEA has been around for nearly 60 years, and is renewed approximately every 10 years. Each time it is revised, it is given a new name: Goals 2000, Every Student Succeeds Act, or, in 2000, No Child Left Behind (NCLB). The ESEA is currently called Every Student Succeeds Act and does away with many of the NCLB regulations — therefore, those who lay the blame for the problems in education on NCLB may need to look at the ESSA more closely.

NCLB was the first time that there were punitive measures against schools and districts that did not show “adequate yearly progress” in academic achievement, or in school behavior issues. Under NCLB, schools that were deemed “persistently unsafe” were sanctioned in progressively harsher ways. As a result, many school superintendents directed administrators to under-report acts of school violence, and to deal with, for example, fist-fights, without resorting to out-of-school suspensions.

This institutional dishonesty resulted in some very interesting efforts to encourage young people to avoid violent behavior. In one school district near the one where I worked, the middle school principal would fly a special flag outside of the school building on days when there were no fights. Other schools adopted school-wide reward programs such as point and level systems that gave students rewards such as weekly movie afternoons if the student had earned enough points to be considered at the highest level of positive behavior.

Many schools seemed to jump onto the positive rewards bandwagon in an effort to encourage positive behavior. We saw systems like “catch them being good” in which adults would give a tangible reward to students who did something positive. We saw “Character Counts” programs in which students were expected to demonstrate one of the six pillars of ethical behavior, and in which students who did demonstrate those behaviors were given a tangible reward of some kind.

The common theme of these programs was to give students tangible rewards if they followed the rules and who were recognized by teachers and staff as “behaving”.

I can almost hear readers saying, “What’s wrong with that? That’s the opposite of punishing misbehavior, isn’t it?”

Well, yes, and no.

Yes, giving tangible rewards like movies, or extra recess, or special privileges, candy, treats, tickets, or whatever, is the opposite of punitive measures that seek to punish those who do not “behave”. But the reality is that these programs do not work either.

We have known since the 1970s at least that giving a person a tangible reward actually decreases their enjoyment of that activity. Daniel Pink, in his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, summarizes these studies from an economics perspective. (I highly recommend listening to or watching Pink’s TED Talk.) But Pink is not the first person to call for end to “stickering students to death” as I used to call it. Alfie Kohn has long been an outspoken champion of making schools less about rewards and more about learning.

I’ve written about this phenomenon before, and I will repeat here: promising treats, extra recesses, or other tangible rewards will not make students more successful. It will not make students adopt the behaviors that are rewarded. In fact, it will make students less likely to see the behavior or academics as something worthy to do, and more likely to make them see those things as means to an end. They will do the minimum to get the maximum reward. It will not make those students who are not rewarded envious enough of the reward to have them change their behavior on their own. It does make students see the reward as handed out consistently to students based on something other than their behavior – for example, students perceive that athletes get rewards more often than non-athletes. It can also result in the same phenomenon reported in Black article, that students see rewards and punishments being unfair and punitively applied to those who really need help.

Dr. Ruby Payne, quoted in an article about the effectiveness of punishment in schools, says that while teachers may see punishment and rewards as flip sides of the same problem, students do not. She goes on to say that behaviorist theory that says to reward one behavior and punish another may work when one is observing rats in the laboratory, or training animals, but it doesn’t work so clearly with human beings. (Morrison, 2014)

Rick Wormeli ,another “big name” in education, comes at this argument from the perspective of making meaningful changes in schools and from standards-based grading. In one of his videos available on YouTube, he discusses the concept of make-up work and assessing students who fail to turn in homework. In it he says, that students who raise their hands, sit down in their chairs, do work when we tell them to do it, do it, not from a fear of punishment, but from hope. He says it is not about “you can get a horse to water but you can’t make it drink. No, it is about you can get a horse to water, but you can’t make him thirsty.” He advocates for making students “thirsty” and to do that they have to have hope. (Stenhouse Publishers, 2010)

So how do we, as Rick Wormeli says, communicate hope to students?

First, we have to change our perspective on what works and what does not work when talking about managing behavior. All of the resources I consulted stated this: We must reform how we manage student behavior, not with punishments or rewards, but by teaching students the behaviors we expect.

Harry and Rosemary Wong have advocated this approach for decades. They say that if we just give rewards or apply negative consequences, we are applying discipline, we are not managing the classroom or the behavior. They repeat over and over again that we must teach students what we expect them to do, not just with academics, but with behaviors as well. (Wong, 2018)

Understand, this is not a quick or easy fix. Many teachers have not received much instruction in classroom management. They have been expected to simply acquire these skills by osmosis or some other process. Those who were required to take a specific class in classroom management often did not really embrace the information. They did what was expected of them, but continued to believe that punishment was the real way to change student behavior. After all, the college students would say, they changed their behavior when their parents punished them.

This last is a misconception about how parents teach children about what to do in any given situation. Parents teach children in several ways that do not include punishments. They demonstrate what they want, using what we educators would call direct instruction. They also employ indirect instruction by modeling expected behaviors – sometimes behaviors educators do not want to see in schools! Parents have children practice the desired behaviors over and over again, primarily because parents have more opportunity to be with children – they are with children when they are not in school and during school vacations. (I am using “parents” loosely, as meaning whomever stands in for parents, including those providing child care.) In addition, parents are usually loved by children, and are far more important to the child than a teacher.

This latter part is especially true if the child has the perception that “the teacher doesn’t like me” or “the school is out to get me.” This is the result of the negative side of the self-fulfilling prophesy, and of being both on the receiving end of school punishments or observing that these punishments are applied in a manner thee student sees as unfair.

I often hear, “By this age, students should know . . . “ Yes, they probably should know, but they have just demonstrated they do not know. Or they may know what Ms. Jones down the hall means or expects but not what you mean by something or what you expect students to do. It may be fine to just toss work onto Ms. Jones’ desk, but you want the work put neatly into a particular tray. You must teach students how to do that! It may be fine in Ms. Jones’ room to holler across the room, “Hey Teach! I need some help here!” It may not be okay with you, and if not, you must teach the desired behavior!

When we teach behaviors, we have to follow the formula we use when teaching how to find the area of a rectangle or the steps in the scientific principle: teach, practice, reinforce, reteach, practice some more, and reinforce again. Just saying do this or do that at the beginning of the year won’t help. Expecting students to remember everything you expect when they’ve had 3 out of 5 days home with snow days, won’t help. We must teach the behaviors, and review them when students have been away from school or in a situation where the expectations have been different for a while. Review expectations after having a sub as well. It doesn’t have to be a big, long review. It can be as simple as, “In just a minute I’m going to ask if you all turned in your homework when you walked into the room. Tell me what it is you are supposed to do when you turn in homework? Jackie? Yes, that is correct, we . . .”

Middle school and high school teachers often describe student behaviors that they find particularly difficult to change. This can be true for a number of reasons.

First, one of my personal rules is “the larger the kid, the larger the behavior.” Behaviors that started out fairly small when the student was in kindergarten have compounded until they are “larger” by the time they are in 7th grade. A kindergartener who throws a temper tantrum is more easily handled than a 7th grader who is nearly the height and weight of an adult.

Second, as children get older, there are more opportunities for life experiences to leave a permanent mark or scar. What may have made a child cry in 1st grade has become so deeply entrenched by 7th grade that it may have completely changed that student’s perspective on life, leaving him/her with chronic depression, anxiety, or other mental health issues. The 7th grader has had at least 8 years of school experiences, making re-learning or changing a behavior that much more difficult.

Third, the peer group has become more and more important. An early elementary student may do something just to have the teacher smile at him. A 7th grader is much more likely to try to get other 7th graders to approve of his behavior.

Fourth, a 7th grader has had far more opportunities to learn what works and what doesn’t work. She may have learned that if she doesn’t like math, she can act like this or that and she will be sent out of the room. He may have learned that if the lunch room is where he will be bullied, he can earn a detention and avoid the lunch room all together. If she think that teachers are usually out to get her, she will see what the teacher does, not what the teacher intends, as reinforcing that belief.

All of these are even more true of the high school student.

One obvious solution would be for specialized teachers to work with disruptive students. I started out as a special education teacher, and that is what we were expected to accomplish. However, I have worked in teacher preparation for 13 years and as a school principal and curriculum coordinator for 12. In the last 15 years, I have seen a troubling trend in special education. That is, these specialists are viewed as people to help students complete work assigned in “regular” classes rather than as having something to teach students separate from the “regular” classroom. More recently I have seen this trend in states or in districts that have a near 100% “commitment” to the integration of special needs children into the regular classroom.

Please do not misunderstand me. I am not advocating for a return to the bad old days when kids with special needs were hidden away in basement rooms and who never saw the rest of the school or their peers except in art, music, and PE classes. (That latter is another story altogether.) What I am saying is that students with special needs in learning disabilities and behavior disorders need to have specialized instruction in how to work with their different abilities. The LD student needs to know how to use his/her strengths to help him/her learn. The BD student needs to learn ways to better control his/her behavior before being out in the general population. Both are areas of instruction that a teacher with a four year degree has had no time to learn.

In teaching a junior/senior class in classroom management, I was appalled to learn that the students knew nothing or next to nothing about working with ADD/ADHD students who do not necessarily qualify for and IEP, let alone knowing how to work with BD students, and nothing about oppositional defiant disorder let alone conduct disorders. Yet they were expected to work with all of these children in the regular classroom often without support from a “push in” special education teacher. Even worse in my eyes was that many were getting additional endorsements in special education besides their “regular” teaching license with almost no additional training.

How can we expect any regular teacher with a four year degree to know what to do about students whose poor behavior has taken root for so many years?

Yes, these students can benefit, sometimes, from having an aide work with them. However, few special education aides have any training whatsoever in working with these students. And what do we expect when we pay them minimum wage for 30 hours a week or less so we can get by without providing health insurance?

Neither is what is meant when we write an IEP that says a student needs an aide or when we say that s/he is eligible for specialized instruction. Folks, that is exactly what it means when we say a student is eligible for an IEP! We are saying the student needs specialized instruction from a teacher trained to work with his/her disability.

Besides the lack of training, many teachers find that the special education teacher is bogged down with far too many students than s/he can teach effectively, even if s/he is only expected to help students complete work assigned by others.

To be fair, those who set the school budget and who oversee the instructional program too often do not have much more training than the regular classroom teacher, and often that training came many more years ago. School board members in many states do not need to have any particular level of education to qualify for the position. They are elected on whether or not their campaign promises strike the voting population as needed or reasonable. And few of the people in a community will vote to raise property taxes to improve school funding.

So we must understand that changing this situation will not bet a quick or easy fix.

There are a few things a teacher can do to help improve the situation. But it will not be a silver bullet! And often, the best time to start these changes is at the beginning of the year.

What we can do:

Relationships

Teachers can and must develop relationships with students. It is not enough to develop a relationship with those students who follow the rules, complete homework, and are generally viewed as “the good kids.” When we do this, we perpetuate the self-fulfilling prophesy. Students live up or down to the teacher’s perceptions of them, even if the teacher does not consciously treat the students differently.

I recommend greeting students at the door of the classroom at the beginning of the day or at the beginning of each class period. When I first heard of doing this, I was teaching science and saw the passing time between classes as the time when I could quickly set up equipment for the next class. I had to revise how I structured my working day, arriving at school a bit earlier and setting up the equipment for the whole day, not just class period by class period. I had to get over my initial feelings of how unfair this was to me, and to focus instead on the students.

I also recommend that teachers work to improve their relationship with students by improving their relationship with the students’ families. Making positive phone calls home is the best way to do that as study after study has shown. Families view a voicemail message as being much more personal than an email, especially when it appears the email is mass-generated. And we still cannot guarantee that adult family members will use electronic media with any regularity! I’ve written about ways to go about making positive parent contacts. When I taught middle school I saw about 120 students a day, but I managed to usually meet my goal of contacting each student’s family by phone once per month. It meant making about 6 phone calls per day. I was always sure to have a quick thing to say, hoping for voicemail, but telling parents who actually answered the phone, “I have about 30 seconds to let you know this” so they would be more understanding if I had to cut the call short.

Although I do not have the article at my fingertips, I recall reading where a teacher would quietly some of the more problematic students as they entered the room, “I’m glad you are here today. I’m planning on calling your mom (or aunt, or foster mom, etc.) today and telling her how you are doing in school so I’m going to be watching you closely today to be able to tell her something good.” It sounded a bit like what I did as a principal. I couldn’t hope to call every family about every one of the 500 children in the building each month, so I picked out those kids who had the worst reputations for behavior and focused on calling home each month with something positive about those students.

I can say from experience as both a teacher, a principal, and parent that those positive phone calls work!

Use Praise and Encouragement, not Tangible Rewards

We know tangible rewards don’t work so don’t use them. Yes, that is difficult when other teachers use them, but it can be done.

When I am talking about praise and encouragement, I am not talking about saying, “Good job, Kathryn”. That is not praise. In fact, most students hear it as so much noise – think how Charlie Brown hears his teacher talking. Others see that “good job” as something other kids hear but that they don’t – more ways we perpetuate the self-fulfilling prophesy.

Useful praise tells the receiver exactly what s/he is doing right and why. Students cannot hope to replicate the behavior if they do not explicitly know what it is they are supposed to do! Here is the formula for effective praise and encouragement:

- Get the student’s attention – usually by saying their name quietly or by talking directly to the student

- Tell the student what s/he has done that is right or praiseworthy. For example, saying, “You were able to hold your tongue and not say something mean to Gloria when she knocked your books down.”

- Tell the student why that behavior is positive. For example, “Remember how when you would yell at the other student, it was usually you that got into trouble? By holding your tongue, you were able to avoid making the situation worse and having you get into trouble.”

- If you can, acknowledge the effort the student made to do this thing. For example, “I know it takes a lot of effort and self-control to do that.”

- Then you can add words of praise like, “that was awesome”, or “good for you”, etc.

It is important that teachers make the praise about the students, not about the teacher. Saying something like , “I like how you did this or that” is not effective because it makes the praise contingent upon what the teacher likes. Students need to know that there is a goal larger than what a teacher likes or dislikes. If it is just about what the teacher likes, we reinforce the perception that teachers are arbitrary and unfailr.

Use Restorative Justice Practices instead of Punishments

There are some very good articles about restorative justice practices found on the Edutopia website. In a nutshell, restorative justice practices focus on helping students make up for what they have done, and learn from the situation rather than applying punishments. Students do not learn from punishments because they are designed to make students fear the negative consequences of a particular behavior rather than learning an alternative to that behavior.

A case in point: many schools use detentions and they do so because they believe students will want to avoid getting a detention. This does not acknowledge that students often do not know how or what to do instead of the behavior that earned them a detention, that detention is often preferable to being with others at recess or in the lunch room, or that often older students have incorporated the idea of being “given” a detention with their personal identity. (Note, in schools that do use detentions, never say you are “giving” a detention. That again reinforces the idea that detentions are awarded in an arbitrary or punitive manner. Instead, always talk about the student earning the detention or “In this school, that behavior means you must go to detention.” Never make the behavior about what the teacher likes or dislikes!)

Too often we think that if this small negative consequence didn’t work then we just need something stronger to use as a deterrent. Not so. Less harsh penalties often have a greater effect on the student than the fear of a harsher one. It is more effective to hold a student after class for a minute or so to talk with the teacher (keep it short!) than to threaten a detention.

Don’t assume! Teach the expected behavior!

I often hear, “By this age, students should know . . . “ Yes, they probably should know, but they have just demonstrated they do not know. Or they may know what Ms. Jones down the hall means or expects but not what you mean by something or what you expect students to do. It may be fine to just toss work onto Ms. Jones’ desk, but you want the work put neatly into a particular tray. You must teach students how to do that! It may be fine in Ms. Jones’ room to holler across the room, “Hey Teach! I need some help here!” It may not be okay with you, and if not, you must teach the desired behavior!

When we teach behaviors, we have to follow the formula we use when teaching how to find the area of a rectangle or the steps in the scientific principle: teach, practice, reinforce, reteach, practice some more, and reinforce again. Just saying do this or do that at the beginning of the year won’t help. Expecting students to remember everything you expect when they’ve had 3 out of 5 days home with snow days, won’t help. We must teach the behaviors, and review them when students have been away from school or in a situation where the expectations have been different for a while. Review expectations after having a sub as well. It doesn’t have to be a big, long review. It can be as simple as, “In just a minute I’m going to ask if you all turned in your homework when you walked into the room. Tell me what it is you are supposed to do when you turn in homework? Jackie? Yes, that is correct, we . . .”

Look for the Positives, not the Negatives

It is very important that teachers always focus on what kids are doing right, not what they are doing wrong. That means recognizing and reinforcing when students take baby steps in the right direction. We do that when we teach kids to do double digit multiplication. We will say, “Yes, you got this part and this part right. Now, what do you do next?” Sadly, we forget that behavior is also something that is learned and changed incrementally. When we look for positives, we are much more likely to see the student who is taking those baby steps in the right direction. We are more likely to notice that student who didn’t yell at Gloria when she knocked his/her books on the floor. We are more likely to get the behavior we want when we actually look for it!

I know this is much easier to say than to do. It takes a true shift in perspective. I used to make little notes to myself, usually in the form of a symbol, and put them where I would see them, just to remind myself to do this and not that. For example, I would use symbols like these to remind myself to use the effective praise formula.

Love the Sinner, Hate the Sin

We have to let students (and parents) know that we really like them. We may not like something they did, but we like the person the student is. We cannot do that unless we focus on the positive!

On a larger scale, there are things schools must do if they are going to turn things around, if the school is going to improve the experience of schooling. It is not going to improve if schools and districts adopt policies that punish students rather than help educate students to live better lives.

Don’t expect that adopting any of the above will change things over night, or in a week, or even in a month. Remember, most students have had too many years of negative school experience to overcome. Indeed many of these recommendations work best if initiated at the beginning of a school year. However, one can make improvements in our own lives as well as the lives of the students by even taking small steps.

Given that the school year is half way done, I would recommend doing the following:

- Make positive phone calls home

- Teach, practice, reinforce (and repeat) the expected behavior

- Hate the sin but love the sinner

I know that I have not addressed all of the concerns expressed to me about this topic, but this blog post is twice the length of any other one I’ve done, so I will have to look at those areas in other posts.

Take a deep breath! You can do this!

Works Cited

Amaro, M. (n.d.). Why Punishment is Ineffective Behavior Management. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from The Highly Effective Teacher: https://thehighlyeffectiveteacher.com/why-punishment-is-ineffective-behaviour-management/

Black, D. W. (2018, March 15). Zero tolerance discipline policies won’t fix school shootings. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from The Conversation: Adademic Rigor; Journalistic Flair: http://theconversation.com/zero-tolerance-discipline-policies-wont-fix-school-shootings-93399

Breslow, J. M. (2012, September 21). By the numbers: the cost of dropping out of high school. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from PBS: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/by-the-numbers-dropping-out-of-high-school/

Bridgeland, J. M., Dilulio, J. J., & Morison, K. B. (2006). The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Dropouts. Retrieved February 17, 2019, from gatesfoundation.org: https://docs.gatesfoundation.org/Documents/TheSilentEpidemic3-06Final.pdf

K12 Academics. (2011). School Leaving Age. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from K12 Academics: https://www.k12academics.com/dropping-out/school-leaving-age

Maxwell, Z. (2013, November 27). The School-to-Prison Pipeline Is Targeting Your Child. Retrieved September 12, 2018, from Ebony: https://www.ebony.com/news/the-school-to-prison-pipeline-is-targeting-your-child-405/

Morrison, N. (2014, August 31). The Surprising Truth about Discipline in Schools. Retrieved February 12, 2019, from Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/nickmorrison/2014/08/31/the-surprising-truth-about-discipline-in-schools/#5bdd6ec93f83

National Education Association. (2012). Raising Compulsory School Age Requirements: A Dropout Fix? (An NEA Policy Brief). Retrieved February 13, 2019, from National Education Association: http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/PB40raisingcompulsoryschoolage2012.pdf

Stenhouse Publishers. (2010, December 14). Rick Wormeli: Redos, Retakes, and Do-Overs, Part One. Retrieved February 16, 2019, from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TM-3PFfIfvI

Wexler, N. (2018, November 29). Why Graduation Rates Are Rising But Student Achievement Is Not. Retrieved February 13, 2019, from Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/nataliewexler/2018/11/29/why-graduation-rates-are-rising-but-student-achievement-is-not/#271c02216a7f

Wong, H. a. (2018). The First Days of School: How to be an effective teacher 5e. Harry K. Wong Publications.