International Women’s Day was March 8. Contrary to what some commercials seem to say, it is not a day to wear pink ruffles and feel nurturing. It was started in 1909 as a celebration of women’s rights, and a way to advocate for more rights. The rights women agitated for at that time included being paid equal to men and the right to vote.

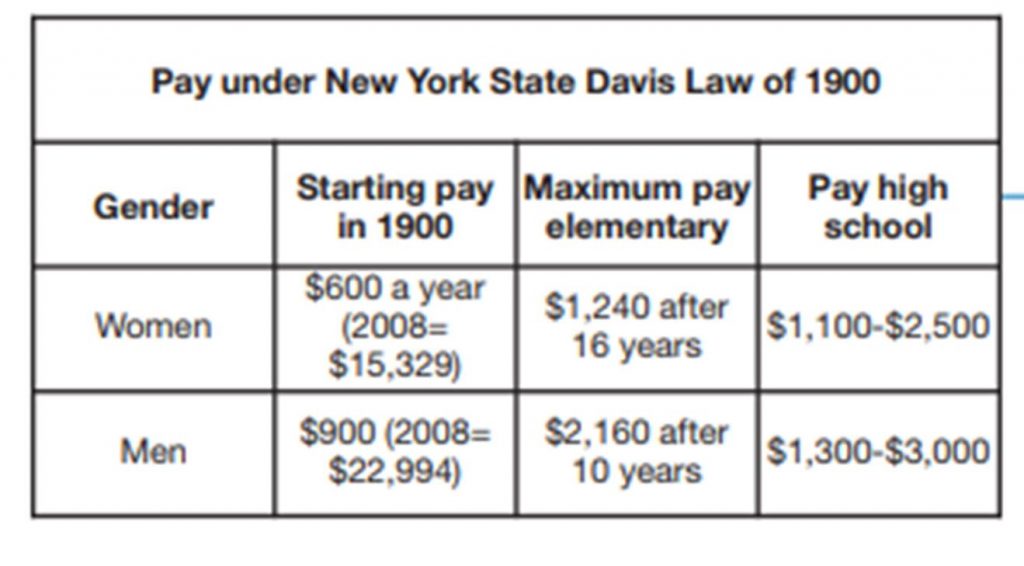

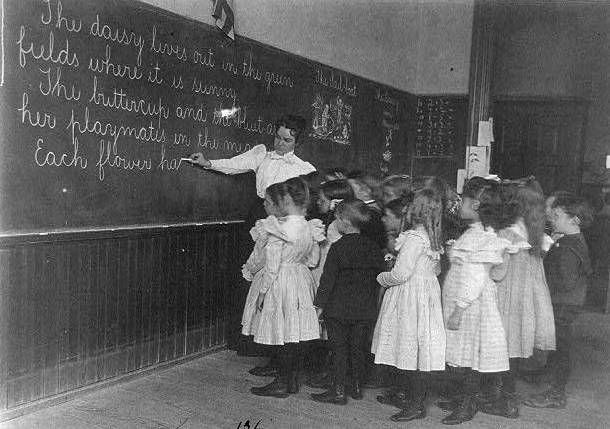

By 1900, women made up 75% of teachers. High schools were not as common as grades 1-8. Many schools had turned to female teachers in an effort to save money. At that time, women could be paid a fraction of what a man was paid, and they could be expected to clean the school as well.

In many areas, a woman could receive a teaching permit by passing a series of tests. In addition, she had to have people attest to her “deportment”, her behavior in the community. She was expected to dress modestly, avoid spending time with men especially if there was no chaperone, attend church, and remain single. She could be fired at the first hint of “immorality”.

I was not born in 1900 even though many of my students seemed to think I was a contemporary of Moses. I have, however lived through some significant changes in education with regards to women’s rights. In honor of International Women’s Day I would like to outline some of the changes I’ve seen during my lifetime. In addition, I would like to remind readers that none of these changes came from above. They were won by teachers fighting for those rights through their unions and, in some cases, through lawsuits.

When I was in high school, girls were required to wear dresses to school. We can thank Mary Ann Tinker , her brother, and her parents for filing a lawsuit against the Des Moines Board of Education for changes to the dress code. The Supreme Court’s ruling was the “students do no leave their Constitutional rights at the school house gate”.

This ruling affected many areas of schooling. For example, I was not allowed to take a drafting class in high school because drafting was for boys only, and, according to the teacher, “Your short skirts would distract the boys.” Girls were not allowed to take shop classes and boys did not take home economics classes. In the latter, we girls were taught to sew, cook, clean, and care for children. Shop and drafting classes were expected to teach boys skills they could use to get a job right out of high school.

In Illinois, I was not allowed to do certain jobs or play sports because of what was called “protective legislation”. That is, the state had passed laws that were supposedly designed to protect a woman’s smaller size and reproductive abilities. In the grocery store where I worked, I was not allowed to stock shelves, a higher paying job than working the cash register, because it would have required lifting more than 25 pounds, the limit placed on women. Playing sports would damage our ability to have babies, or so the lawmakers said. We could watch Iowa girls playing basketball and softball on TV, but Illinois would not allow it.

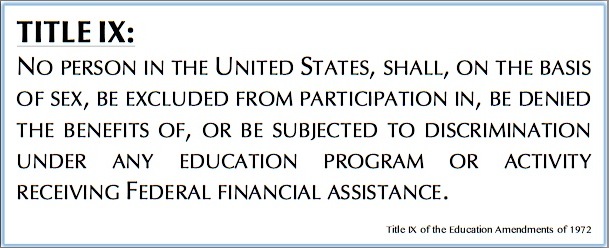

It was not until I was out of high school, in 1972, that Title 9 was passed. Among other things, Title 9 said that girls had to have equal opportunities for sports. Girls did not have to have the exact same sports available to them, but they needed to have something so that there was balance. For example, boys played football while girls played volleyball.

Schools were supposed to provide equal amounts of money to each sport. Some schools got around this requirement by using booster clubs to pay for “additional” expenses.

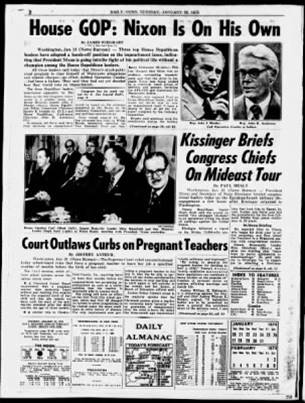

It was not until 1974 that female teachers won the right to be visibly pregnant in the classroom. Prior to the Supreme Court’s decision in Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur, most school districts required women to stop teaching before the 4th month of pregnancy and to remain on leave until the child was a specified age. Usually women were not guaranteed to be reinstated in the classroom. Instead, they were supposedly given “given priority in reassignment to a position for which she is qualified”. In other words, before the Supreme Court ruled on this, a woman had to quit teaching if she became pregnant and she couldn’t count on getting her job back again even with the required doctor’s certificate that she was healthy enough to work.

When I applied for my first job in 1978, I had several shocks.

The first came during my first interview. I met with the superintendent of schools. There was no committee or model lesson to teach. It was just the two of us with him asking questions and me nervously answering. I needed this job to support my husband and me! I was stunned when he asked me what kind of birth control I used. I must have looked at him strangely because he explained that he didn’t want to hire someone who would be going on maternity leave right away.

Now, that question is considered illegal. And he would not have asked it if I were not married. Why? Because an unmarried teacher was not allowed to be pregnant at all.

The latter situation was covered under what were called “morality clauses” in teaching contracts. In these, signing the contract showed the teacher’s agreement to not do anything that was considered immoral by public standards of the time. Immoral behavior could mean becoming a single mother, living with a man she was not married to, drinking or becoming drunk in public, or even public displays of affection. It could mean wearing one’s skirts “too short”, or clothing that was too tight. It could mean being gay, being arrested, taking part in political demonstrations, having an extramarital affair, or talking back to the principal. In short, immorality could mean anything the school board said it meant.

Many teachers learned to live outside the school district, and to be very careful when in public. Nonetheless, I received a reprimand from the Board during my first year as a principal in the 90s. I was painting my office and needed some supply or other. I ran out to WalMart wearing my paint-covered, grubby clothes. This was not, the Board said, the way a principal behaved.

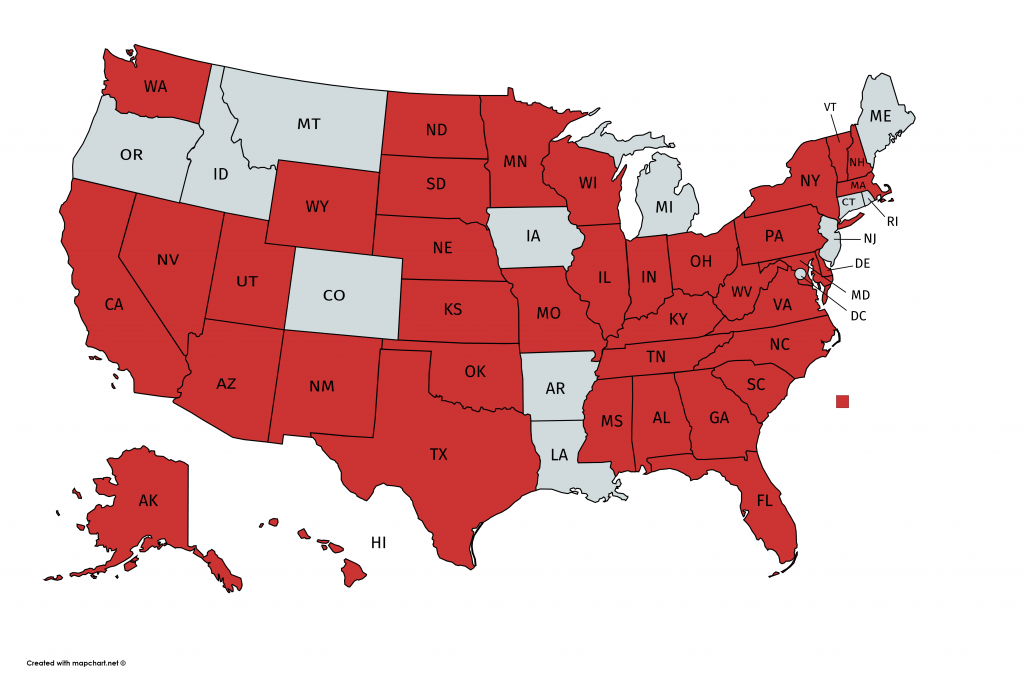

When researching for this blog post, I was surprised but not shocked to find that in many states even today teachers may be dismissed for not conforming to the community’s “morals”.

Dress codes continued to be strict for at least another decade after that embarrassing first interview. Female teachers had to wear skirts or dresses, which meant wearing nylons and “appropriate” footwear. Some places were so strict that I learned to take out three of my five earrings as having multiple ear piercings could be construed as too racy. There was no getting away with other piercings, or visible tattoos. And one could not wear denim except on very special occasions. When I moved to a district that allowed women to wear “dress slacks”, I felt like I’d been given a marvelous gift!

After I got divorced, I could not get insurance for my son through my work. The policy was set up for singles or for families, and a mother and son were not considered a family. Birth control was not paid for through my prescription drug coverage until we entered the 21st century!

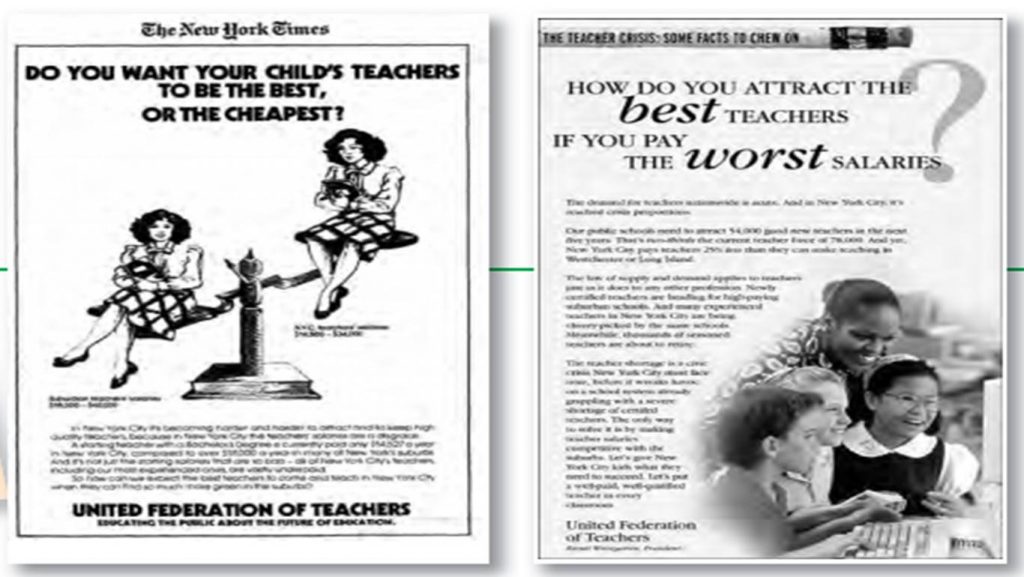

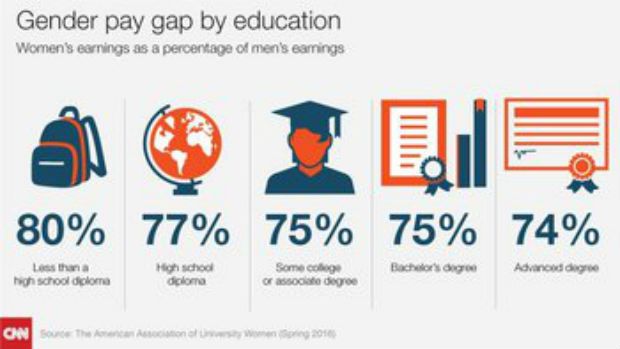

We still have not achieved equal pay for teachers from PK to 12. The gap is closing and is much narrower than when I first began teaching. Back then we were told that elementary children are easy to work with and that to teach high school one needs more education. Even then that argument didn’t hold much water. To the best of my knowledge, we haven’t had elementary teachers who got their teaching license after attending a two year school – the equivalent of an AA. When I first became a principal, I had a couple of elementary teachers who had such degrees, but they were ready to retire. Yes, high school teachers take more in-depth classes in a single subject, but elementary teachers take more classes in more subjects and more in-depth classes in pedagogy. I think anyone would be hard pressed to try to argue one was a more difficult job than the other.

Unions have helped a lot to achieve parity between the grade levels!

There is still a lot of difference between the pay principals at each level receive. Women are still under-represented in administration, and because individual principals negotiate their contracts individually, they can still be offered less than a male counterpart. In one district I was told that the brand new elementary principal would be receiving half again as much money as I was making even though I was working with a higher grade level and I had four years of experience. I was told flat out that the difference was that I was a single woman and he had a family to support. I don’t think anyone would be that blatant to say it so blatantly now. At least I hope not.

Things have changed a lot for women since 1900, and I’ve only been around to see a fraction of those changes. I haven’t even touched on things like women’s suffrage, the laws that finally allowed women to own property in their own right, being allowed to have a credit card in our name, or being allowed to prepare for any career we want. I haven’t mentioned the college professors who brushed women aside saying we were in college only to get our MRS (to get married). I haven’t mentioned the constant struggle women felt when it seemed everything in the world was against us. I’ve only brushed the surface with my little trip through educational changes. I probably forgot a lot more of them!

I didn’t describe how difficult the struggles were to achieve those changes. Just think about it: It took the better part of a century to do this, and it has taken the last 50 years to make most of the changes I’ve described. It would be very easy to lose the gains we’ve made. Think of that when you listen to the news or when your local district negotiates its next contract or when your state contemplates making changes to education law.