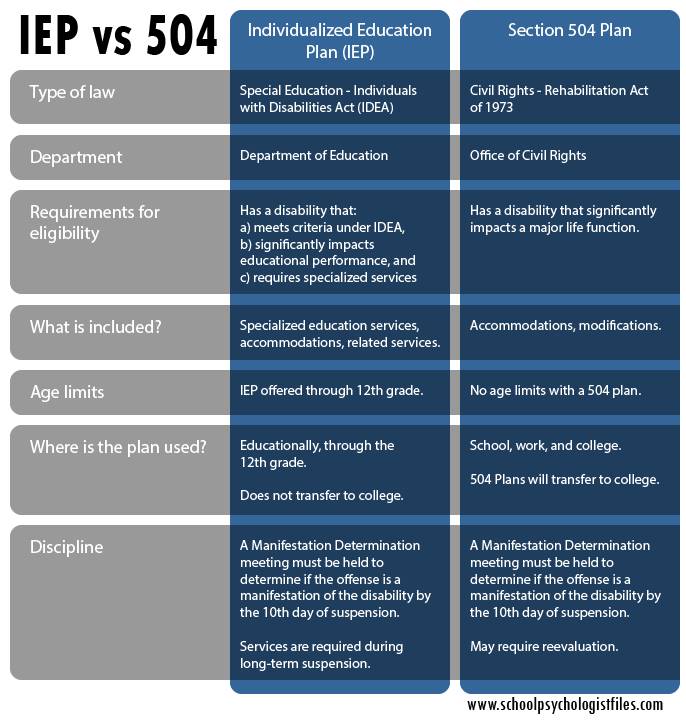

December 3 was World Disability Day. For many people, disabilities are something visible, or something a teacher would encounter in an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). That is true for some disabilities, but not for all.

Those of you who know me know that I am hearing impaired. Being hearing impaired means having a nearly invisible disability, and having one that is often misunderstood.

I lost my hearing as an adult. I caught a cold and my ears never recovered. Yes, they did surgery, and no, it didn’t help. I was teaching at the college level at the time and I did not tell students or colleagues to begin with. As I discovered how little people understood hearing impairments and how much a lack of hearing affected the one with the impairment, I began to tell people. I would let classes know about my hearing impairment on the first day, but I wouldn’t always say something later on when I didn’t understand something someone was saying. I even had a couple of classes where students purposely would mock my inability to hear. (Gee, I wonder why I didn’t think those students should become teachers!)

I decided I needed to help future teachers understand hearing and not hearing better. I began to pass out foam ear plugs and encouraged students to try a class using one in one ear. Many were astonished how much diminished hearing in one ear could affect their comprehension of the class. I taught them a bit about how we hear and how we can lose part of our hearing. I taught them about what hearing aids can and cannot do. Many told me that they’d always be taught that hearing aids meant the person could now hear like “normal.” Nothing could be further from the truth!

In retrospect, I could have done more to educate my colleagues. But there is a part of me that wonders why I’m the one who is responsible for educating others.

If you are not standing near me at just the right angle, you might miss seeing my hearing aids. That is not because I am trying to hide them, because I don’t. Hearing aids today are easy to miss. The parts that hook over the ears, like mine, are smaller than they were in the past. Some people have hearing aids that are completely inside the ear. The only clue for them is the tiny bead that is at the end of the part that helps the wearer remove them from the ear.

If you do not see my hearing aids, you may miss the reason why I want to sit in a particular part of the room during a meeting. I am an adult and know where I need to sit to have a better chance of hearing the speakers. However, I will not try to do so if I’m met with resistance, or if I have to ask every time we have a meeting. I won’t ask, but I will become resentful that my colleagues are not more understanding. As time goes on, and that attitude is likely to color other interactions.

If you do not see my hearing aids and we are in a large meeting room, please do not say, “I don’t need the microphone. I have a loud voice.” You may have a loud voice, but I probably need both the amplification and to be able to see you to understand most of what you are saying. I may be bold enough to say, “No, I need you to use the microphone, please.” Many people are not so bold. They may wind up staring out of the window or playing with their phones, not because they are rude but because they can’t understand what’s being said.

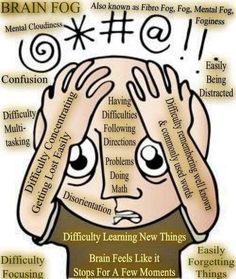

If you do not see my hearing aids, you may keep talking to me when you’ve turned away so that I cannot see your mouth. Many people think hearing aids make it so the wearer can hear everything that goes on. Hearing aids do not give back “normal” hearing. A hearing impaired person relies on many things to know what a person is saying. They may need to actually see you, to be able to partially read your lips and to see your expression. Hearing aids may help mask tinnitus, but they do not make it go away completely.

If you do not see my hearing aids and I ask you to let me see what you are saying, you may just try to raise your voice. That doesn’t help much. Yes, hearing aids boost the volume of sounds, but those are only the sounds the person can hear. There are sounds that are now higher than my ability to hear and lower than I can hear. Just talking louder will never make me hear those sounds better.

If you do not see my hearing aids and I tell you I am hearing impaired, you may be tempted to talk louder and slower, and to use single syllable words. My hearing loss has not affected my intelligence. You do not need to simplify what you are saying. I assure you, my intelligence will allow me to understand complex concepts. I just need to be able to hear you or to see you in a way that allows me to read your lips.

If you do not see my hearing aids, you may not understand why I am so reluctant to use the telephone. If you see my hearing aids, you may not understand either. Telephones are strange things to me. Sometimes I hear the other person very well. Sometimes I do not. It has to do with the timbre of the person’s voice. For example, I can hear one of my grandchildren just fine, and another I cannot understand at all. My personal telephone uses an app that translates messages from voice to text. I’ve asked for this to be part of the telephone system at work only to be told the system cannot do that. Inside my own head I was angrily snapping, “Maybe it should!” But I didn’t want to make more waves. Yes, there are devices that allow totally deaf people to communicate using telephones, but I am not that profoundly deaf.

If you cannot see my hearing aids because you are calling me on the phone and you want to leave a message, please do not rattle off the phone number you want me to use to call you back. It is highly embarrassing to have to ask a student to listen to a message and have them write down the phone number for me! You don’t know if the person for whom you are leaving a message is hearing impaired or not. It is only polite to state your phone number is a way that the listener has the best chance of understanding it.

If you do not see my hearing aids and you are talking about a current movie that I have not seen, do not assume I do not like movies. I like movies a LOT. I just cannot go to theaters that do not offer closed captions. There are a lot of theaters that do not, and there are a lot of hearing impaired people who are too shy or too timid or too irritated to ask the theater for that kind of help. Many theaters have young workers who do not know what to do with a hearing impaired person and may do any of the above when they are told you are hearing impaired or they may just act like being asked if they offer devices for the hearing impaired is a burden. It often makes it a hassle to even try, so I tend to wait to see movies when they come out online.

If you do not see my hearing aids, or maybe even if you do, if I ask you to repeat what you’ve said, please do not sigh, or roll your eyes, or become exasperated. I wouldn’t ask you if I didn’t need to.

If you do see my hearing aids, you may think that all I need is to have the sound turned up. I’ve even had movie theater workers tell me to just turn up my hearing aids. I’ve been told the theater, or church offers sound amplification devices. Amplification doesn’t help if the sound itself is out of my hearing range. Nothing could be further from the truth. The problem may be that the sounds are out of my range of hearing, but there may be other issues as well. Even though I’m hearing impaired, I am sound sensitive. That means that loud noises and/or certain frequencies are like fingernails on a chalkboard. There are sounds that make me yank my hearing aids out of my ears that fast! (Come to think of it, young people may have no idea of what fingernails on a chalkboard sounds like!)

I’ve been told to go to events even if I cannot hear what is going on. How many people will go someplace to sit without understanding what is happening for several hours? Would you?

If I am in a hotel, I will want to be able to turn on closed captions to be able to watch TV. I’ve been in some very classy hotels that do not have this ability on the room’s remote. I’ve had to call the desk and have someone with the “normal” remote come and turn on the closed captions. I’ve been in some where the clerk has just told me that they don’t have closed captions available. It is both embarrassing to ask and exasperating to have to ask. Maybe those hotels should advertise that they do not cater to hearing impaired people – oh, but that would be against the law, wouldn’t it?

Even if you know I’m hearing impaired, you may question why I have a handicapped tag for my car. Part of my hearing impairment has affected my balance. I’ve had people question my use of handicapped spaces enough that I am tempted to affect a limp when using the handicapped parking spaces. Lately I’ve decided that I’m a big girl and I can tell when I’m having troubles with my balance and when I’m not. I am the only one who knows when I need to park closer. But that means I’ve had to try very hard not to see people’s faces or to not hear them tell me the handicapped spaces are for people who are “really handicapped”.

That brings us back to invisible disabilities. There are many of them. People who suffer from depression or anxiety may not be obvious. They may take medication and still be depressed or anxious so telling them to take a pill can be insensitive, and can make them more depressed and more anxious. We may not be able to see vision problems, autism, ADHD in adults, chronic illnesses, or learning disabilities. That does not mean these disabilities do not exist.

Too often we’ve been lead to believe that disabilities mean something obvious. In the 1970s when legislation was passed in the US requiring accommodations for children and adults with disabilities, we started seeing changes in textbook images and characters on TV. Largely these images show people in wheelchairs or using crutches or white canes. It is no wonder that we think of disabilities as something we can see.

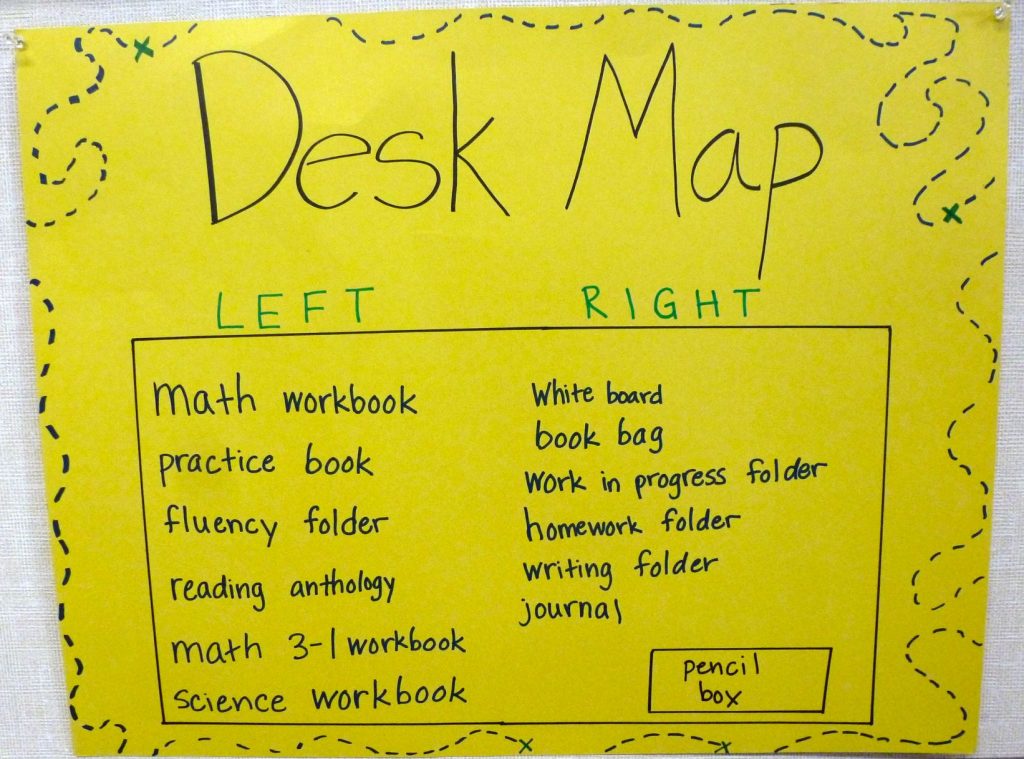

I have been in education for 39 years. I’ve had the opportunity to observe how children and adults with disabilities are treated. If the student is learning at the same pace as his/her peers or if the disability does not require a teacher with specialized training, his/her disability does not have to be recognized through an IEP. There may be something in the student’s file suggesting preferential seating, but that may be it. Children are not always the best advocates for themselves. They don’t know how to ask for more. They also do not always know that there can even be something that would help them in the classroom, hallways, lunch room or playground. (I have a great deal of trouble in lunchrooms. The background noise prevents me from hearing. The sound can overwhelm my hearing aids. And my noise sensitivity may make it so I am overwhelmed.) A child’s disability can even be a source of embarrassment. I recall children who hid their glasses, or pocketed their hearing aids to try to be “normal.” I even worked with an albino student who refused to wear her sunglasses, and always tried to sit in the sun – she cried and said she just wanted to be like everyone else. Doesn’t every child?

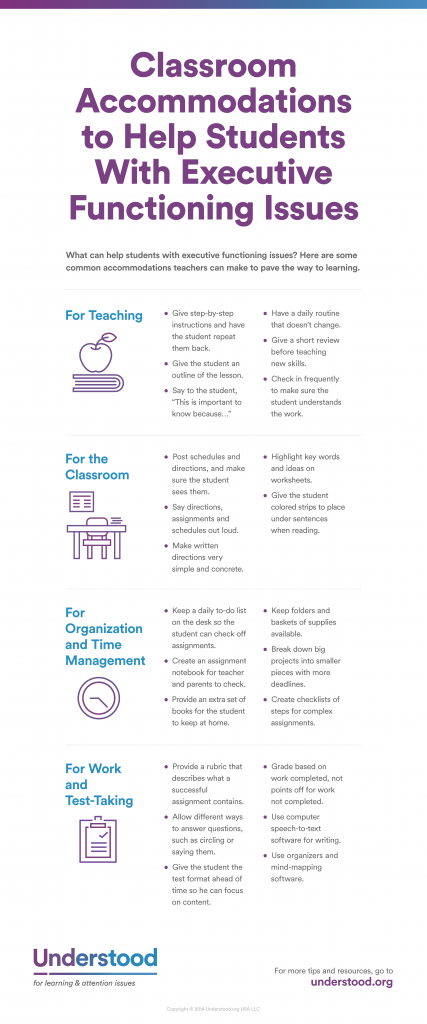

If you are an educator, you may now be thinking, “Well, those kids should have 504 plans!” For those of you who are not in education, a 504 plan is a legal document that outlines the accommodations a student needs to be successful in the classroom. Students are eligible for a 504 plan if their disability does not require specialized instruction, but who need some “extra” things to reach their potential in the classroom.

In every school district in which I’ve worked, there has been great resistance to developing 504 plans. I asked one superintendent why he would tell me to not allow 504 plans. He said it would mean too much pressure on teachers and gave parents too much ammunition to “helicopter” their children, to not allow the children to learn without the parent hovering over them.

Yes, a 504 plan does require school districts and teachers to provide those accommodations to students. It does allow parents and others to hold teachers accountable for those accommodations. Yes, it does allow parents to legally advocate for their children. And why shouldn’t educators be willing provide those accommodations?

If teachers have not received training in how to best work with a child with a 504 plan, they should be encouraged to get that training. The school district should provide that training. If the parent is willing to work with the teacher, the teacher should not be shamed by the school district or the parent. I know from experience a four year degree does not allow enough time to learn everything a teacher needs to know!

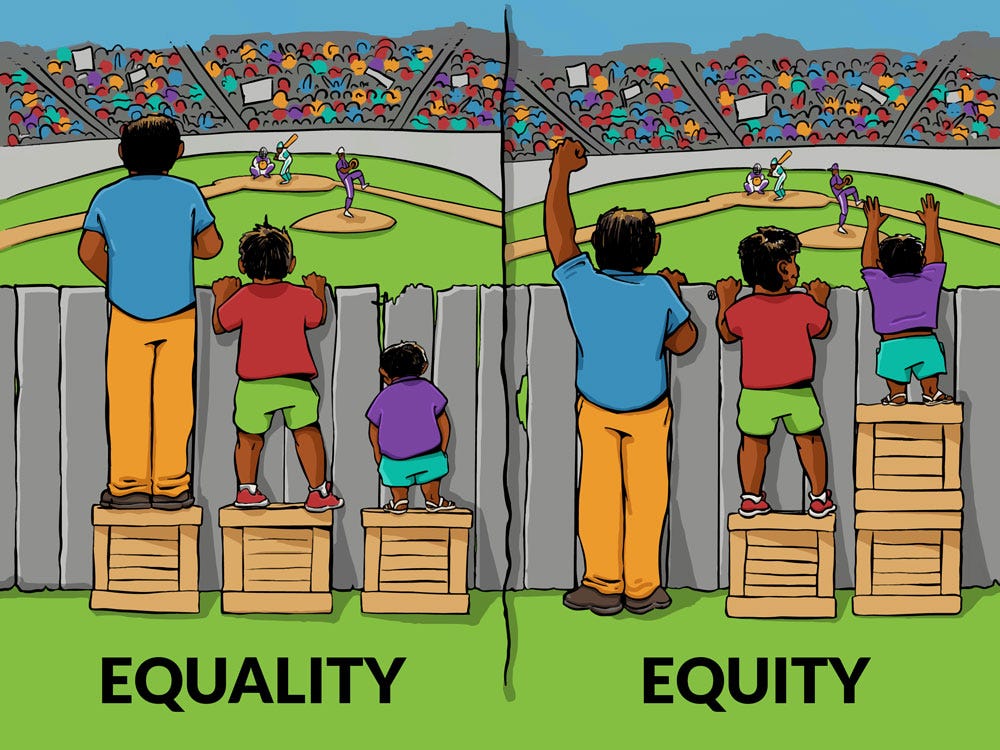

The real point here is that we don’t know who does and who does not have a disability. We should not wait to provide accommodations until someone asks. We should not assume everyone around us is completely able-bodied. If we aspire to being a kinder society, we should assume someone in any given group will need some accommodation. And we should provide those accommodations without someone asking us to do it, without the law forcing us to do it, and without shaming the persons who need them.

So the next time I say, “Pardon me, I didn’t hear what you said”, please just look at me and repeat it. Don’t sigh, or roll your eyes. Don’t raise the volume of your voice and talk to me like I’m not bright. Don’t make me always have to fight to be able to know what is going on. And, frankly, don’t always make me ask!

When you come right down to it, all I’m asking for is to be treated with dignity and welcome. I think I deserve it and I think everyone else deserves it too!