Have you ever had to pry yourself out of bed in the morning and shuffle off to school even though you’d rather stay home?

Have you ever had to make polite small talk with someone you really do not like or do not respect?

Have you ever felt crabby and irritable when you were in a situation where you couldn’t express that?

Have you ever had a period in your life where you weren’t particularly happy with yourself?

Do you ever have days when your best is far less than your best on other days?

I’m sure you could say yes to all of the situations described above. I certainly have! There have been many days in my life where I’ve had to paste a smile on my face when I really wanted to pout or stomp my feet. There have been many times where I have had to “fake it ‘til you make it” at work or in other parts of my life. And I have had periods in my life where I was not pleased with myself but was still expected to meet my obligations, when my “best” was nowhere near as good as my capabilities.

Let’s face it: It is not always easy living out lives! And most of us have learned that we cannot always show everyone what we are thinking or feeling.

The students who come to us for six hours or so every day often have the same difficulties, but they are not as mature as we are and often cannot fake it. Not all of them are able to overcome their inner emotions and present a more perfect front to the world. It is equally true that some will have learned to fake it rather than let a teacher know what they are really thinking.

Well, duh? Right? What does this have to do with classroom rules?

There are very well-meaning teachers who make rules that they themselves would not be able to follow. They make rules about emotions, things that are not really observable or measurable.

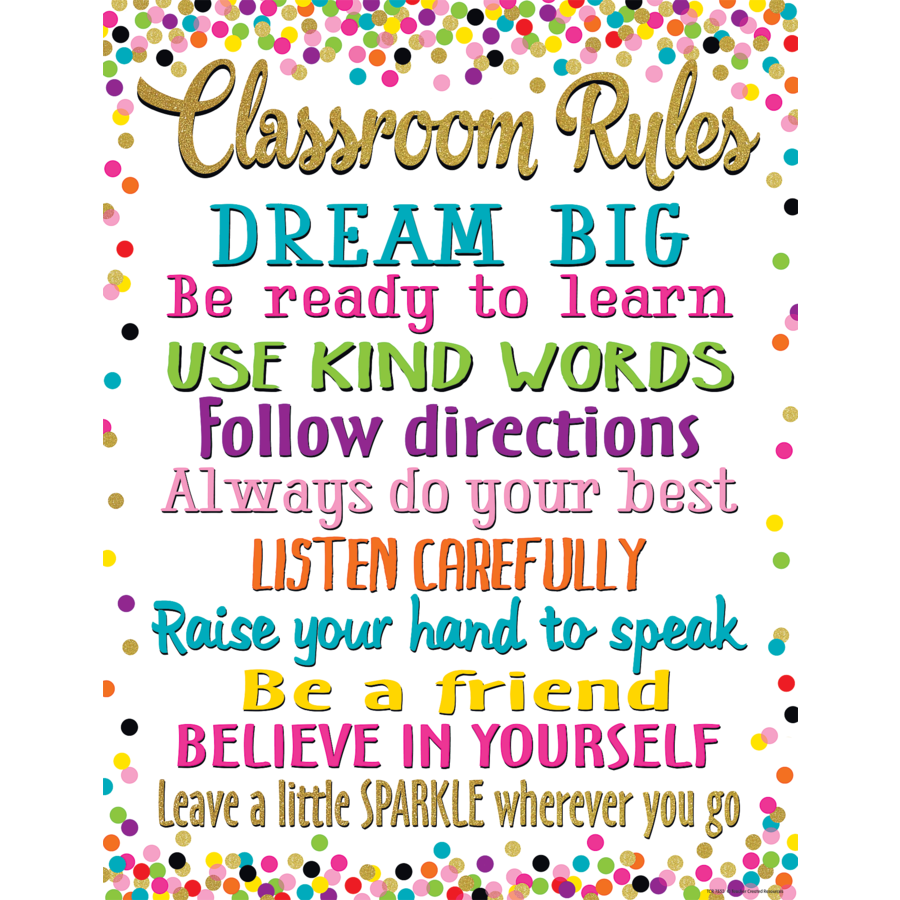

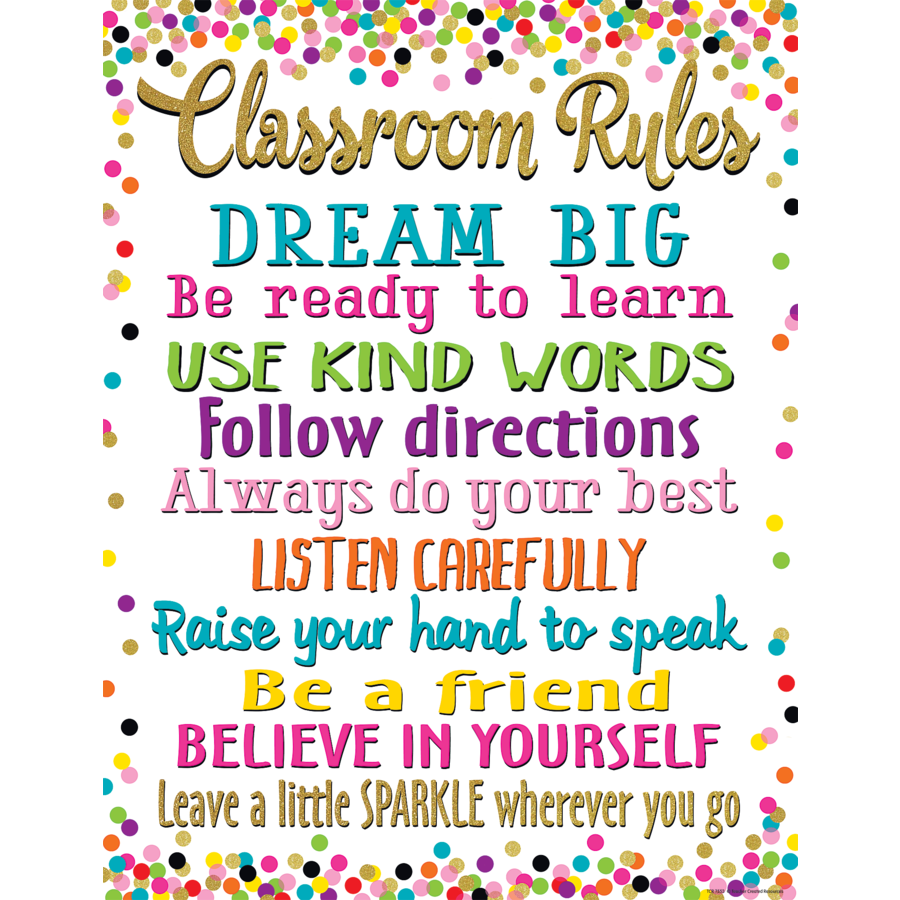

I used this commercially available rules poster as an illustration last week and I labeled some of the “rules” as really being goals.

Let’s look at these a little more closely.

Always do your best. How do we know if what a student is doing is his/her very best or the best s/he can do right now?

Believe in yourself. How do we know a student believes in him/herself?

The answer to both of those questions is we don’t. We honestly do not know if anyone believes in him/herself. Sure, we can see certain behaviors that make us believe that Susie believes in herself, but we really don’t know for sure.

You might say, “a student who believes in herself would keep trying when they find something difficult” or “he would turn in his homework because he would know that his school grades matter” or “she would wear clean clothes and have better hygiene if she believes in herself”.

All of those behaviors might lead us to think the student doesn’t believe in himself. But we cannot know for sure. We cannot see inside any student’s head to know what s/he is really feeling or thinking. In fact, many of the students who come to us every day have learned, sometimes painfully, to fake it.

Let me try to clarify.

What is going on with the student in this photo?

You might say the student is tired, or isolating himself, or that he is bored, maybe angry. You might say any of those things and you might be right. You can cite your experience that says that when a student has his head down on the back of a seat like that he is feeling this way or that. And you might be right. But you might not be.

You really cannot know for certain what is going on inside a student’s head. Yes, this one might be tired, or sad, or bored, or angry. He might be isolating himself for a reason that has negative connotations. But he also might have a headache. He could be overwhelmed by the noise around him, or trying to control his emotional reaction to something, or he could be hungry. He could just be tired of holding his head up!

In fact, the site where I found that image had it under “bored child’, “angry child”, and “sad child”.

My third point about classroom rules is that the rules should be about things that are observable and measurable. If we make rules about thoughts, attitudes, or emotions, we will be forever chastising students. And we can be wrong about it, too.

Take this young lady. Is she engaged because she is “ready to learn” as the rules poster says? Does she believe in herself?

She does appear to be doing what she’s been asked to do if she was asked to do some school work.

Appearances can be deceiving.

Once I had to deal with a first grade girl who, by all appearances, seemed to be a model student in the classroom. On the playground, she was far from well-behaved. She was the leader of a group of girls who were terrorizing other girls. This young lady was actually a bully who was directing others to carry out her bullying behavior. When I talked to her about it, she informed me that she wrote out plans for who she was going to tell to do what to whom. She had it all plotted out in a notebook in her desk. When I asked, the teacher told me that this little girl “loved to write” and would get done with her work early so she could spend time writing stories. The teacher had to see the bullying plans the girl had written to believe she could be at all involved in this playground behavior.

This was an experienced teacher and not one that was easily fooled by students. However, this little girl had the teacher snowed.

We just do not know what is going on inside other people.

I often see rules that say something about “respect yourself”. I understand what the teacher is getting at when they have this as a rule. The teacher believes, perhaps correctly, that a person who respects themselves will treat others well and will do what they need to do to make their aspirations come true. However, I also know that children who are abused often present a “perfect” front to the world outside while inside they have little respect for themselves. I’ve worked with young people who are “cutters”, who cut themselves to relieve stress and painful emotions, yet few of their teachers knew anything was amiss.

I often see rules that say something about “have a good attitude”. Again, I understand that the teachers are trying to say that the students should act like they want to learn, that they should be willing to try new things, or to persevere when learning something that is more difficult. I want students to do that, too. Yet, we cannot know if students have a good attitude. We can only know if they appear to have a good attitude.

We make rules about ‘respect the teacher” when we really do not know if they actually respect us. We just want them to treat us as if they respect us. We make rules about “make friends” not because we really think everyone needs to be friends with all 500 or 2000 kids in the building, but because we want them to act in a friendly manner. We make rules about “have fun” not because we think that memorizing multiplication tables is all that fun, but because we want them to learn to love learning.

We don’t expect teachers to have fun all day long, or to be friends with all of the adults who work in the building, or to respect even the most bumbling of colleague or administrator, although we do expect them to treat that person respectfully. We certainly “have a good attitude” all day long, every day. So can we really expect students to do so?

That’s what we are usually trying to get at when we make rules that are about things that are not observable or measurable. We want students to behave as if those things were true.

How can we hold students accountable for such “rules”?

I asked that of a group of college students in a classroom management class. I was told, angrily, “I’m not an idiot! If a student is having a bad day, I won’t force him to follow that rule!”

If that pre-service teacher meant she would be sensitive to the students’ needs, then more power to her. But if it is a RULE, then we are obligated to hold students accountable. Thinking back to the traffic laws analogy in previous posts, a police officer is rarely, if ever, going to say, “Oh, wow. You are having a bad day, so I’m not going to write you a ticket for exceeding the speed limit or rolling through that stop sign.” If it is the law, a rule, then it is in place at all times even if we don’t feel like following it.

(Yes, there is something called civil disobedience, but that is something else. Come on, don’t rain on my analogy!)

Let’s say you did allow Fred off the hook for not following the rule “Have a good attitude.” The other students in the room observe what happens when Fred tells you that he is having a bad day, and you do not follow through on enforcing the rule. The next time you try to hold Herman accountable for that rule, he tells he is having a bad day. You really cannot dispute it because you don’t know what went on before Fred got to school and you don’t know how he is really feeling about it.

Teachers may believe that they are trying to be equitable and responsive to students’ needs by enforcing the rules sometimes and not other times. However, I would be willing to bet that, even though the teacher means well, s/he begins to enforce the rules in a way that reinforces the self-fulfilling prophesy, being flexible with some students and inflexible with others based on his/her perceptions about that student.

We all know what happens if a teacher is not consistent about enforcing rules. Students begin to resent the fact that the rules apply to some, but not all. They try to argue about fairness. And they begin to test the teacher every day – is today a day when the rules are enforced? Or is today one of the days when they are not? Are they enforced for this student and not for that?

That is a recipe for chaos.

In addition, students live up or down to their perceptions about the teacher’s beliefs and attitude towards them.

Take a look at your list of classroom rules. Do any other them deal with things that are not observable or measurable? If so, what behavior is it that you are trying to get students to do? Is there another way to get that behavior?

I used to tell students to “give me the appearance that you are paying attention to me. Look in my direction. Nod your head sometimes.” Of course, I said it humorously, and the students laughed, but there was a bit of seriousness as well. If a student was doing something that made it appear that he was not paying attention to me, I would make another joke about it and most of the students would comply.

Think about how you might get students to do X besides making a rule about it.

We’ve looked at four of Roe’s Rules for Rules so far:

- Rules must be about things students can actually control or know how to do.

- Rules must be about things that are reasonable.

- Rules must be in place at all times.

- Rules must be about things that are actually observable and measurable.

We will look at another aspect of rules next week.