It is easy to say “no” to that question, but the reality is that some teachers are afraid and some teachers should be afraid.

How can both be true?

Why some teachers are afraid of parents:

- Many teachers do not like confrontation.

Sadly, some parents are habitually hostile towards teachers. These are the parents who assume that whatever has happened, it is the teacher’s fault. They call and are rude or holler. They show up in the classroom, looming over the teacher in an attempt to intimidate. Those parents can be scary! - Some teachers fear parents because they are pretty sure they have done something that wasn’t quite right. Maybe they did scold the wrong child. Maybe they did make a mistake when correcting a paper. Maybe they weren’t as polite as they could have been. Maybe they were a bit too harsh.

- Maybe they really did do something wrong!

We’ll circle back to this in a bit.

Why some parents are afraid of teachers.

- They had bad experiences with teachers when they were children.

Maybe teachers did not help them, compared them to siblings or blamed them for things that were not their fault. Maybe they were told they’d never amount to anything. An adult who was alienated from education as a child will be unlikely to see educators as trustworthy. - They think teachers will blame them if their child is not well-behaved, learning at an acceptable pace, etc.

Sadly, teachers DO blame parents! Teachers seem to classify many parents into several categories:- parents who don’t care and who, therefore, don’t discipline their children, or who ignore their child’s education, or needs. They don’t show up for conferences, do not answer emails or return phone calls. These are also, according to some teachers, the ones who dress their children in dirty clothes, clothes too large or two small, or not appropriate for the weather. They seem too busy to get school supplies, or who take children shopping on a school night instead of doing homework.

- Helicopter parents who hover over children. They are the ones who never let children make decisions. They call and holler about a first grader earning a poor grade because it will allegedly keep the him/her out of a good college. They do their child’s homework, or make excuses for their child.

- Indulgent parents who seem to only want to be their child’s friend. These are the parents who don’t potty train children before kindergarten, who let children stay up late or sleep in, the ones who do not discipline children, or the ones who buy the child everything under the sun.

There is another group of parents that is rarely mentioned: parents who are legitimately concerned about how their child is treated in school.

A parent I know has a child who has a genius IQ and a learning disability. She does not have an IEP because she has been able to earn “acceptable” grades despite the learning disability. That is, she’s been able to earn a D rather than an A.

What this child does have is a 504 plan.

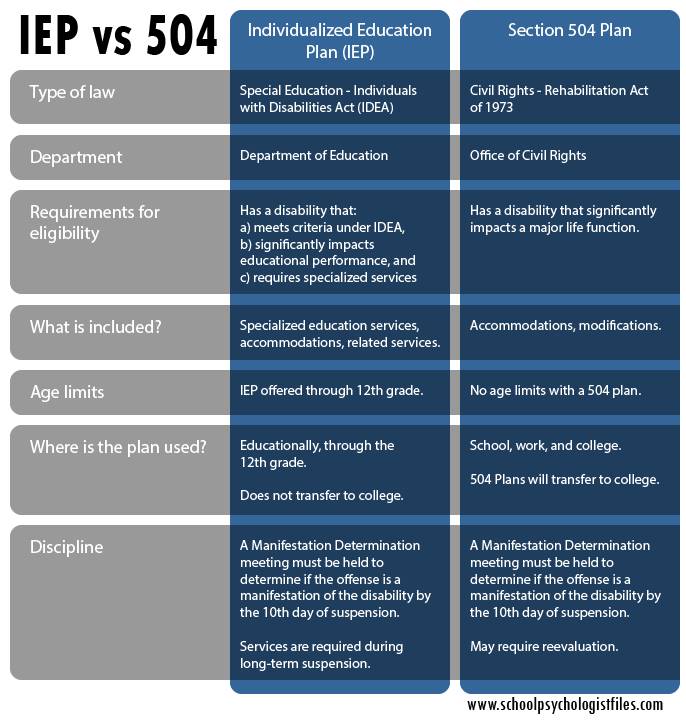

Let’s take a little aside here and explain the difference between an IEP and a 504 plan. Both are legal plans that define accommodations for legally recognized learning differences. The Individualized Education Plan (IEP) defines the kinds of specialized instruction and related services the child is supposed to receive. A 504 plan does not require specialized instruction. It defines the accommodations that will ensure the student’s academic success and access to the learning environment.

So the main difference is that one required specialized instruction from a person trained to deliver that kind of instruction or services. A 504 plan requires accommodations to instruction that can be delivered by a “regular” teacher.

The child has a recognized learning difference, but only needs accommodations, not specialized instruction, to ensure her academic success and full access to the learning environment.

The problem is that almost to a person, none of this child’s teachers have honored the 504 plan! And she is now in high school!

The parent is not a helicopter parent. She is not an indulgent parent. She is certainly not alienated from education; she has a master’s degree and beyond. We certainly cannot say this parent doesn’t care, ether. Yet she has been accused of all of the above by teachers.

All she wants is for teachers to do what the 504 plan says they are supposed to do.

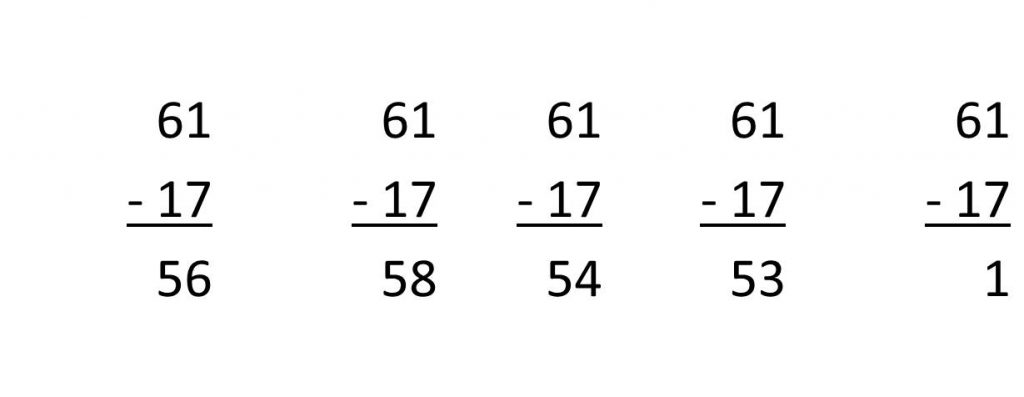

The teachers have given a number of reasons why they haven’t done this.

- They didn’t know she had a problem.

- They don’t know how to do the accommodations.

- They don’t see why she needs accommodations.

- They say they think the mother is just trying to have the daughter’s grades inflated.

- They say they don’t have time to make those accommodations.

Quite frankly, these teachers have simply frustrated both the parent and the student. And the parent is angry.

So back to the original question: should teachers be afraid of parents?

- They SHOULD NOT be afraid if they

- are reaching out to all parents to let them know what they’ve noticed that is good about their child.

- genuinely like students.

- welcome parents as allies in the child’s education.

- have a good relationship with parents and make a mistake like those described previously.

- Keep parents informed of concerns before concerns grow too large or have gone on too long.

- They SHOULD be afraid if they

- Don’t actually like all students

- Don’t respect parents.

- Aren’t doing what each student needs to be successful.

- Aren’t following the law.

Teachers go into teaching to make a difference. None that I know would ever say they are teachers to damage children or to make their lives miserable.

Sadly some teachers become jaded. Some are frustrated with working conditions, administration, or students whose needs challenge their know-how. Some develop beliefs that they know better than anyone else what a student needs. Some may be right, but none should deny a student accommodations designed to help that child be successful.

If a teacher has a student with a 504 plan, find out what accommodations are. Ask colleagues for help on how to do this if you don’t know how. And above all, work with the child’s parents.