Last week, I discussed some trends in curriculum, focusing on “pacing guides”.

This week, we look at technology.

The U.S. Department of Education says:

Technology ushers in fundamental structural changes that can be integral to achieving significant improvements in productivity. Used to support both teaching and learning, technology infuses classrooms with digital learning tools, such as computers and hand held devices; expands course offerings, experiences, and learning materials; supports learning 24 hours a day, 7 days a week; builds 21st century skills; increases student engagement and motivation; and accelerates learning. Technology also has the power to transform teaching by ushering in a new model of connected teaching. This model links teachers to their students and to professional content, resources, and systems to help them improve their own instruction and personalize learning.

https://www.ed.gov/oii-news/use-technology-teaching-and-learning

One cannot dispute the fact that technology can open up a world of information accessible at our fingertips. In fact, I am not at all sure what I would do without being able to check email, touch base with people around the world through social media, or relax while watching a streaming service.

However, does technology itself live up to the promise of engaging and motivating students, teaching 21st century skills, all the while saving school districts money?

Let’s look at these in turn:

Technology saves money – online textbooks are cheaper than buying paper and ink textbooks.

There is no doubt that online textbooks save districts money. Paper textbooks cost money to print and bind. Online publications do not have to include those costs.

In addition, online texts can incorporate video and links to further information.

Some studies claim that about three quarters of students (K though college) prefer reading digital textbooks. However, many of these studies have been funded by online publishers, so we have to take those findings with a grain of salt.

Other research has a more dire warning: if one is reading more than 500 words, the equivalent of a very short article, then one is more likely to retain the information when one reads from an old-fashioned paper textbook. ( https://hechingerreport.org/textbook-dilemma-digital-paper/ ) Despite this, students themselves tend to believe they retain more from digital sources.

More research needs to be done, especially research looking at kinds of reading (informational or fiction) and age groups.

The research right now, though, shows that more learning takes place when reading an actual textbook.

Using technology is supposed to prepare students for the 21st Century

There is an assumption among educational thinkers and curriculum directors that the so-called “digital generation” consume information best through screens. Further, they assume that because the digital generation uses technology so much that they understand it, know how to use it, and are acquiring 21st century skills.

As a former college professor, I can attest to the fact that there are young people who do, indeed, know and understand technology. Yet there are even more, in my experience, who do not.

Further, the digital divide is real. Some families have not embraced technology because of poverty or beliefs. Some live in areas where WiFi is unavailable, prohibitively expensive, or patchy at best. Others belong to cultures that put more emphasis on face-to-face or personal communication and interaction.

These lines seem to be along racial, cultural, and economic lines.

In my opinion, even those who have had access from a very young age rarely understand technology at the level professed by those who describe the so-called digital generation.

The ability to use social media and download music do not mean that one has 21st century skills! I have had college students who do not even know how to change the margins of a paper, let alone how to determine whether or not some tidbit of information found online is true.

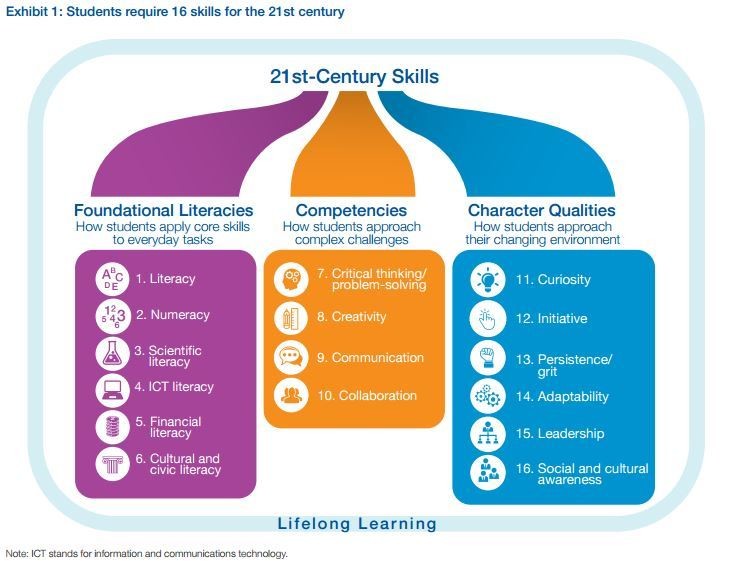

Bri Stoffer ( https://www.aeseducation.com/blog/what-are-21st-century-skills ) lists the skills employers want and need. She says these are

- Critical thinking

- Creativity

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Information literacy

- Media literacy

- Technology literacy

- Flexibility

- Leadership

- Initiative

- Productivity

- Social skills

Note that only points 6 and 7 really refer to technology.

In fact, the very expensive private schools, the Waldorf schools, do not use much technology at all. In Silicon Valley, parents say “technology can wait”, that their children need to learn much more than how to use a computer. ( https://www.cnbc.com/2019/06/07/waldorf-schools-teach-without-technology-heres-what-it-is-like.html )

If the twelve points above are the skills employers are seeking and companies predict they will need when this generation begins their careers, then we educators have much more to do than wrestle with whatever the “flavor of the month” technology is!

Technology is supposed to engage students.

Educators were given multiple reasons why, supposedly, technology was supposed to cure the twin ailments of disengagement and apathy. Yet if my K-12 teacher contacts are correct, then technology has exacerbated those problems: students use their “one-to-one” devices to engage in almost everything except academics throughout the school day, and mobile phones have become teachers’ worst nightmare.

In fact, recent studies show that having a cell phone in the classroom, even if it is turned off, kept in a pocket or backpack, or turned face down on the desk, poses a distraction. ( https://www.edutopia.org/video/theres-cell-phone-your-students-head ) These studies say that students are able to concentrate more fully on class when their phones are out of the classroom altogether.

Why? Our brains are not constructed in a way that allows for them to multi-task despite the belief of many. Instead of really multi-tasking, our brains merely flip back and forth between tasks. Each time that “flip” occurs, the brain must recall what it was doing and refocus on the task at hand. Doing this actually decreases the ability to “deep focus”, the mental state needed for learning and for creative problem-solving.

Other studies have shown that a screen, any screen a student has is distracting to other students in the room. It seems we just cannot take our eyes off of those screens!

Please do not take all of this as a condemnation of using technology in schools! I do not think that is the answer at all!

What I am saying is that we cannot expect technology to be a panacea for all educational problems. In fact, I would recommend that our curricular focus should extend beyond using technology for technology’s sake. Instead we must help students with the following:

- Knowing how to use technology beyond causal skills.

- Knowing how to use technology wisely and ethically.

- Understanding how to evaluate the information they see online or read in traditional sources.

- Knowing how to study efficiently and effectively.

- Learning the whole spectrum of 21st Century skills.