Most of us learned a little about children with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in college. For example, I learned that kids with ADHD couldn’t stop moving and would fidget and squirm in their seats and could not concentrate on anything longer than a few seconds. My professors told me that these children would calm down when given an amphetamine like ritalin, while those who did not have this disorder would “speed up”. I was taught that the best place in the classroom for this student was right up front, next to the teacher. The idea was that if he was sitting there, he would know the teacher had her eye on him and he would control his behavior. And I was taught that setting up a system of negative consequences and rewards would get him/her to control his/her behavior once and for all. Further, I learned from various sources that ADHD is a “made up” disorder and that what looks like ADHD is really the result of bad parenting or inappropriate school curriculum.

Does this sound familiar to you? What if I told you that all of the above were myths?

Myth 1: ADD and ADHD

are “made up” disorders.

The truth is that these are both recognized mental and physical

conditions. People with ADD or ADHD have

meaningful differences in their brains, how they process information, and their

impulse control. ADD and ADHD are neurological

disorders that have been around for a very long time, but were not recognized

as a particular health issue until the last 50 or 60 years. Even then there were some who labeled children

with symptoms of the disorder as “lazy”, “stupid”, “incapable of learning”, etc.

Myth 2: Children with

ADD or ADHD are lazy, stupid, or just plain bad.

It is estimated that the majority of children with ADD or ADHD are above

average in intelligence. They sometimes

appear less capable because the work they are asked to do does not hold their

attention, or because they are wiggling and squirming when the teacher wants

them to pay attention. They sometimes

get the label “lazy” because they do not do school work for a variety of

reasons or lose it before they can turn it in. And ADD/ADHD is not a character flaw. It is a neurological disorder.

Myth 3: If a child

has ADD or ADHD, s/he just needs to take medication.

First of all, the “test” of ADD or ADHD is not whether or not the child

responds to amphetamines in a particular way is outdated. Doctors who specialize in ADD and ADHD have

much more sophisticated ways of determining whether or not the child has the syndrome.

Second, medication works for some children, but not for all. Some children cannot tolerate the medication, meaning the side effects are dangerous. For some, those side effects can include an inability to eat, an inability to sleep, increased blood pressure, nervousness, increased irritability when the medication wears off, headaches and stomachaches, moodiness, and overall increased irritability. The result is that not every person can tolerate the various medications that are used for ADD or ADHD. And the medication has little to no effect on some.

Third, sadly, our schools cannot control all of the bullying that takes place. Children who must go to the nurse at particular times of the day to get medication are often the butt of bullying behavior. Some of the language of that bullying has crept into our everyday language: “take a chill pill” or “did you forget your meds today”. This is a reason why some families choose to not medicate their children.

Myth 4: ADD or ADHD

is the result of bad parenting.

Parents can do everything completely right and still have a child who struggles

with his/her ADD or ADHD. Yes, there are

parents who let their children “get away with murder”, and there are parents

who are too strict with their ADHD children, but the syndrome is neurological,

not the result of childhood conditioning.

However, it is true that having a child with ADD/ADHD can get to a parent’s last nerve. It can put an enormous strain on the family and can result in parents trying every which way to cope with their child. This can result in being too harsh, too indulgent, and even in seeking “cures” from both good and fraudulent sources.

I recall one family that would bundle their child off to the doctor every time they received a negative phone call. They would ask the doctor to give the child different medication each time. Sometimes this happened a couple of times in a single week. The parents believed that medication would create a cure instead of making controlling behavior a little bit easier. It certainly did not help the child.

Parents who are caught up in trying desperately to find a way to cope with their “atypical” child really need help from the school rather than blame. Telling the parent whenever the child has done something the teacher finds unacceptable puts further strain on the family. Many, if not most, parents experience that as blaming the parents and they can respond with guilt, anger, or frustration. That, in turn, can alienate parents from the school, and make them believe that the school, and the teacher are “out to get” their child.

What parents really need is to hear when the child does something good. If the teacher has not started the year out this way, it make take some serious effort to look for and find good things to tell families about THAT student, but the rewards are great.

Myth 5: A child with

ADD or ADHD needs parents and teachers willing to use strict behavior

modification.

Behavior modification is when a person receives negative consequences when s/he

chooses to do something like act out, and receives rewards when s/he chooses to

do something “right”. The problem with

this approach with children with ADD or ADHD is that word “choose.” ADD and ADHD are neurological disorders, not

the result of choice. Some children may

benefit from some negative consequences, but the majority do not. After all, if one cannot choose to have one’s

brain respond in certain ways, how will a detention or a phone call home

(common negative consequences) help? If

one cannot choose how one’s brain responds, how will a trip to the “treasure

chest” or a sticker (common rewards) help?

The use of this kind of behavior management system may help in the short term, but it does not help in the long run. Many with ADD or ADHD have said that they could never get a reward, that they tried their very hardest but they were only punished over and over again. The result of this is often that the child learns to hate school, to believe the teacher is out to get him. It can also backfire. Some students over time become willing to accept negative consequences as a badge of honor.

What many of us learned in college, to have the child sit up front and next to the teacher comes out of this thinking. However, many classrooms do not have a “front” and a good classroom manager is not going to remain in the front of the classroom or at his/her desk. Putting a child with ADD/ADHD up front can have a negative effect on the whole classroom because it puts the child and his/her behavior where everyone can see it. This can break down the child’s relationships with peers.

I abandoned this strategy after having a class that consistently pointed out what the child with ADHD was doing: “Ms. Roe! He’s doing it again!” I finally realized I was the grown up in the room and that I was much more capable of ignoring fidgeting, squirming, and seat dancing to an imaginary tune better than the children. I moved that child to the back corner where fewer of his peers would see what he was doing. I also resolved to allow him to do all of those “hyper” behaviors unless he was disrupting the class. Life became so much better for me and for that particular student!

What the children need to learn most is a set of strategies s/he can use to cope with the demands of school, and to reach his/her learning potential.

Myth 6: It’s not

ADD/ADHD if the child can pay attention to something and not to others.

Many with ADD/ADHD demonstrate a behavior called “hyperfocus”. This means that s/he is so fixated on a particular

thing that is it is difficult to change to another behavior. With my son, it was electronic screens –

video games or computer screens. He used

to describe it as being sucked into the screen.

To change his focus, I would have to literally get between him and the

screen. Like many with ADD/ADHD changing

that focus was difficult and often resulted in angry behavior.

We see this in the classroom when a child does not respond well to changing activities. She may continue to work on that math problem even after being told to put math away and get out the science book. He may whine or act out when told it is time to stop one thing and start another. Children with ADD/ADHD often benefit from having a quiet timer set up so that they can see how much time is left for an activity, or by the teacher telling the class, “We will be cleaning up in 5 minutes so start getting yourself to a stopping place.”

Children with ADD/ADHD also tend to perseverate. That means they will continue to do or say something even after the time for that behavior has passed. For example, the child may repeat a word over and over again, or look for a lost paper in only one or two places because the paper should be in one of those two spots even though it is not in either of those locations. Sometimes this can look like OCD behavior. That can be alarming for a teacher the first time they realize that it is perseveration, but please remember to use compassion – the kid just really cannot help it.

Myth 7: ADD/ADHD is

really the result of a poor curriculum.

Teachers are not really in charge of curriculum. They are hired to teach the district’s

curriculum. But, if you are a teacher,

you already know that. I think maybe the

people who say that mean “teaching strategies” rather than “curriculum”.

There may be some truth to the idea that there are some teaching strategies that are better for kids with ADD/ADHD. Lecture classes, or classes where students are expected to “sit and get” are probably less suited to them. However, there is a good argument to say that those type of classes are not good for most students.

My advice is to remember this “Roe’s Rule”: The person who does the most work is the person doing the most learning. That is, if the teacher is doing the most work, then the students are not doing the most learning. Instead, creating lessons where students do the work is most likely to result in them learning the most. For example, when I was teaching, the state said every eighth grader was to have a course in Indigenous People in the state. The social studies teacher complained that she wouldn’t have time to teach everything else if she had to teach all of the “stuff” the state said the kids had to learn about Indigenous People. I suggested that she form the class up into groups and have each group learn about a particular group, then teach the rest of the class what they learned. That could be done in several different ways including a Jig Saw method.

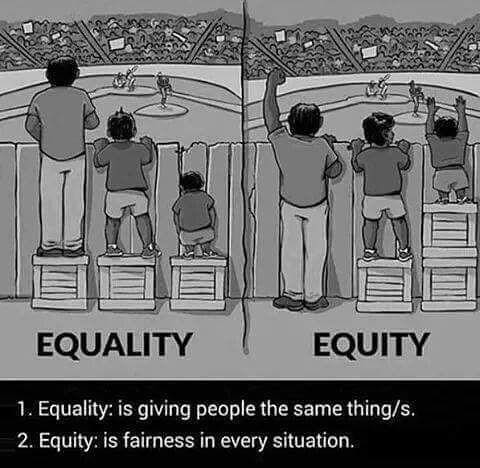

There are many myths about people with ADD/ADHD. We educators need to keep learning about this and other conditions that make a student different from the so-called typical student. As a nation, we tend to pride ourselves on all being individuals, so shouldn’t we look at each of the students in our class as individuals? Equity doesn’t mean treating everyone the same. It means treating each in the way they need most.