He’s just lazy.

She just wants attention.

He is sneaky.

She doesn’t care.

We’ve all heard these statements or ones like them. And they are true, aren’t they?

Well . . . maybe.

Apparently, human minds are wired to be able to speculate about what others are thinking or feeling. When she was a cognitive neuroscientist at MIT, Rebecca Saxe discovered there is a specific part of the brain that becomes active when we think about how others think and feel (TED Talk, 2015). Some scientists have hypothesized that the human brain evolved to be able to do this as a survival skill, an essential skill that enabled humans to determine if another was friend or foe. However, experiments demonstrate that we do not always get it right.

Let’s try our own experiment.

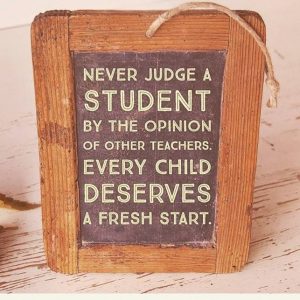

Take a look at this photo of something you might see in your classroom:

What’s going on with this student?

Did you say he’s bored?

Working with pre-service teachers (aka, college students), I found that the majority said this student was bored. Some said he was tired. When asked why they said that, the students would say they could tell by the way he was sitting, or the expression on his face.

But do we really know what is going on in this kid’s mind?

When I was a principal, there were teachers who were very frustrated with a student. “She’s lazy!” they said. “She’s always daydreaming!” “When I call on her, I never know if she is going to answer or just stare at me.” “Sometimes she looks at me like I’m not even there, like she’s boring holes in my with her eyes.” The teachers complained to me and to the parents.

These parents wondered if something else might be going on. They took their daughter to the doctor, to a psychologist, and other specialists. Eventually, they asked to set up a video camera in the classroom. The camera was rigged so that the students would not know if it was on or off, and the student was filmed over the course of a week.

The result was that this little girl was diagnosed with petit mal seizures. She wasn’t bored, or daydreaming, or staring holes in the teacher. Her lack of attention was not something she was doing on purpose. She had a serious medical issue — one that might not have been discovered if the parents had only relied on the opinion of the teachers.

So let’s look at this photo again. What is going on with this student?

Well, yes, he could be bored. He could be tired. He might have a headache, or have a neck injury, or just being hungry. He could be frustrated that he was not called on. He could be trying to keep up with the lesson even though he doesn’t feel well, or even though he doesn’t understand everything being said.

Would it make a difference in our beliefs about what this student is thinking if we were told he is a second language learner? If we were told he was moved from one foster home to another in the middle of the night? If we were told he had an IQ of 140?

The teachers who described the little girl who had the petit mal seizures thought they were accurately relaying information about her. They were not trying to be malicious or trying to deal with her unfairly. Sadly, they were labeling what they thought was going on rather than reporting exactly what they were seeing and hearing.

Back when I worked in juvenile corrections, I was trained to report only what was observable and measurable. This was a difficult thing to learn to do, but it was essential to how this particular institution dealt with the students/inmates. Why? Well, because we really do not know what is going on inside another person’s mind. We may pride ourselves on our ability to read body language or to spot “tells”, but we don’t always get it right.

On top of the chance at being inaccurate and unfair, when we use terms like “lazy”, “unmotivated”, “day-dreaming”, or “bored”, we are demonstrating that we have formed an opinion about the motives of the student, and that reveals the opinion we have formed about him or her.

In a previous post, I discussed how we form opinions of students that become self-fulfilling prophesies. We develop an opinion about how capable the student is and then we treat her a little bit differently based on those beliefs. We might call on her less if we think she is not as capable of answering a question. We smile less at those students we believe are less capable, and we talk to them differently. In short, we create a very different socio-emotional climate in the classroom for the students we believe are “good” or “better” than we do for those we believe are “less capable” or “naughty”.

However, if we are not always accurate about what we think is happening with a student, is that opinion fair?

Probably not.

The fact is we cannot see what is going on inside a student’s head. The expressions and body language for many feelings and emotions are quite similar.

Perception is reality.

If you are perceived to be something, you might as well be it

because that’s the truth in people’s minds.

Steve Young

This phenomenon is something linguists have been exploring since the 1930s: The words we use and how we label things shapes our thinking about those things.

Adults are usually better at masking what they are thinking than children are. Adults have usually learned to pretend to pay attention, to be engaged, even when their brains are actually planning a grocery list, thinking that the speaker’s hairstyle is unflattering, or when thinking about how happy they will be so see their significant other later in the day. But children do not have that skill, and while many will learn it as they enter adolescence, not everyone does. Human brains do not reach full maturity until age 25 or so.

So what is the take-away? If we have become frustrated with THAT student, we might find ourselves labeling what THAT student is doing as being something negative when it really might not be. That negative opinion will have an effect on how we treat him or her, and how we treat THAT student effectives his or her behavior until s/he lives up or down to our opinion of him or her – if we believe s/he is a trouble-maker, s/he will become a trouble-maker even if s/he wasn’t beforehand.

Yes, humans are wired to make assumptions about others based on what we see, but we must remember, sometimes we get it wrong.

If we really want to turn THAT student around, we have to train ourselves to report on just what we see and hear, what is observable and measurable.

One has not only an ability to perceive the world but an ability to alter one’s perception of it; more simply, one can change things by the manner in which one looks at them.

Tom Robbins

We will look at some other uses for using observable and measurable terms in another post.